El chileno Jorge Montealegre (1954) es periodista, poeta, ensayista, investigador, gestor cultural, especialista en humor gráfico, directivo de la Red de Investigación y Estudios del Humor (RIEH), Chile y redactor creativo y guionista de humor gráfico. Trabajó mucho tiempo haciendo chistes, por ejemplo, para las publicaciones humorísticas Condorito y Topaze.

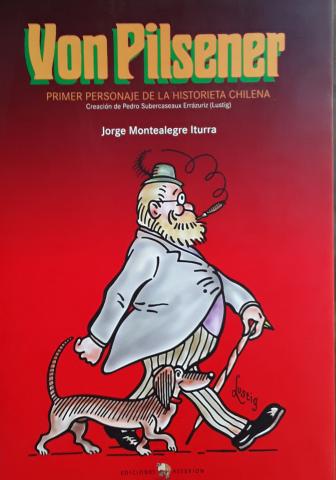

Ha publicado unos cuantos libros, entre ellos: Von Pilsener, primer personaje de la historieta chilena; Puro Chile. Sátira humorística y (anti)patriótica, Prehistorieta de Chile, del arte rupestre al primer periódico de caricaturas y Sentido del Rumor. Monitos y monadas bajo dictadura.

Lo han premiado en innumerables ocasiones. Obtuvo la Beca Guggenheim (1989), que le permitió escribir Historia del humor gráfico de Chile.

Pero para mí, además de ser un gran creador de humor y de un excelente estudioso del humor y aparte de un reconocido poeta y ensayista (su carrera “seria” es muy exitosa), es mi amigo. Fue el primer humorista que conocí cuando llegué a Chile. Incluso hemos hecho cosas juntos en el humor.

Por todo ello, estoy contentísimo de tenerlo aquí en este vis a vis.

PP: Querido Jorge, presentándote recordé las “Noches Cacheras” en tu casa. Para aclarar: invitabas a muchos amigos a jugar cacho, como pretexto para conversar un vinito entre todos y reírnos mucho. Extraño esas reuniones. En esas noches conocí a unos cuantos importantes humoristas chilenos como Hervi, Gai, de la Barra y otros. Espero que si reanudas esa tradición me vuelvas a invitar, ¿de acuerdo?

JORGE: Más de alguien pensó que las “noches cacheras” eran una especie de orgía. Se decepcionaron. El ceviche que aportaba Hervi es inolvidable y para qué decir la “torta de panqueques” que hacía Pía. Un asistente regular, también del ámbito del humor, era Pancho Zañartu. Muy buen guionista, de “Los Venegas” y otros programas. Hernán Venegas era un Venegas en vivo y en directo (dibujante de la tira “Entrelíneas”. Infaltable. En fin… los dados y el cacho fueron buenos pretextos para juntarnos y pasarlo bien. Y reírnos.

PP: ¡Mi querido Zañartu, claro que sí! Bueno, después de ese lindo recuerdo, comienzo ya el interrogatorio: ¿te presenté bien? ¿Me faltó algo que quisieras agregar? Y más allá, ¿cómo te gustaría que te recordaran?

JORGE: Muy generoso. Soy un autodidacta con doctorado.

PP: Un autodidacta con máster sería yo entonces. Bueno, ¿cómo llegaste a interesarte en la creación, la investigación y el estudio del humor?

JORGE: Cuando en 1981 publicamos -sin autorización- la revista “La Castaña”, Luis Albornoz hizo una sección que consistía en un tumulto de personas de las cuales salían globitos de diálogo y pensamiento sin texto. En blanco. Como yo era el editor literario, me pasó los dibujos y me dijo que a mí me correspondía llenar esos vacíos. Yo venía de la poesía, muy parriana, así que copié algunos textos del Perich y me atreví a inventar algunos míos. Muy luego los hice todos yo, sin necesidad de copiar. Me convertí en guionista porque esto le gustó a la editora del suplemento dominical de La Tercera y luego esa empresa publicó el diario La Cuarta. Y con el gran Eduardo de la Barra como ilustrador hicimos la sección “Sentido del Rumor” y un montón de otros trabajos, entre ellos al personaje “Palomita”. Esta incursión en el humor me permitió conocer humoristas gráficos que siempre había admirado (Palomo, Hervi, Themo Lobos, Nato, los hermanos Vivanco…) y me di cuenta de que tenían muchas historias y una Historia que ellos no escribirían. Entonces comencé a investigar. Y sigo en aquello.

PP: Me encanta que sigas investigando con la misma pasión. Es trabajo precioso e importantísimo el que haces. Te envido (sana o insanamente). Ahora teoricemos más, ¿qué es para ti el humor? (Me refiero a tu definición del mismo y a qué significa para ti).

JORGE: Sin entrar en las antiguas e inconclusas distinciones sobre el humor, la risa, lo cómico (que ocupó a Bajtin, Bergson, Freud y otros pensadores); de manera simple entiendo el humor como una cualidad humana, inteligente, que permite percibir y crear situaciones risibles que provocan diversas emociones algunas de las cuales se expresan con una sonrisa interior o carcajadas. Al interior del humor me ha interesado especialmente la sátira y sobre ella sí he ensayado una definición: considero que la sátira es una representación crítica, irreverente y burlesca de la realidad. Crítica, porque manifiesta una opinión, generalmente disconforme, respecto de lo representado. Irreverente, porque desacraliza; resta formalidad a situaciones consagradas como dignas de un trato solemne. Esta irreverencia rompe o disminuye las jerarquías (se niega a la reverencia) haciendo el diálogo más horizontal: todo aquello que es susceptible de ser homenajeado puede resistir una mirada satírica. Es decir, puede ser reducido a la precaria humanidad que nos asemeja a todos. Burlesca, porque detecta y revela los aspectos cómicos que encierra la situación -producida sin intención humorística- y los expone a la risa pública con mordacidad. Por último, la sátira es una representación de la realidad, porque tiene un anclaje en ella y propone asociaciones pertinentes con dichos o hechos reales, perspectiva que incluye, devela, ese porcentaje de ridiculez que tiene todo lo que hacemos.

El humor gráfico –a pesar de la frivolidad o falta de seriedad que podría connotar- funciona como un complejo fenómeno sociocultural al interior del cual se pueden abordar diversas aproximaciones que transitan entre lo histórico, lo sociocultural, lo estético, e inclusive desde sus dimensiones patrimoniales y folclóricas. En su variedad, las representaciones gráficas del “pueblo chileno” -mediáticas en su origen- se han infiltrado e instalado en la tradición y cultura popular, configurando una amplia iconografía humorística, que se ha ido diversificando en la medida que se amplía el acceso al consumo de los trabajadores y la sociedad es crecientemente más compleja. La revisión de esta iconografía evidencia que generalmente la exhibición de cada personaje representativo perdura en el tiempo descontextualizada de los procesos históricos y sociales que han originado los estereotipos y caricaturas.

PP: Eludiste un poco tu definición de humor, pero la de la sátira la disfrutaste. Gracias por esa “clase magistral”. Ahora, te iba a realizar una pregunta, pero ya la respondiste. Te la hago igual a ver qué respondes… Si un extraterrestre llegara y como nunca ha visto una obra de humor gráfico (ni una caricatura, ni una tira cómica, ni una historieta, ni nada parecido y te preguntase “¿qué es el humor gráfico?”, ¿cómo tú lo definirías para que lo entiendese?

JORGE: Primero le preguntaría que le parecen los macianos, los ET y los alien del humor gráfico y trataría de explicarle que el humor gráfico –a pesar de la frivolidad o falta de seriedad que podría connotar- funciona como un complejo fenómeno sociocultural al interior del cual se pueden abordar diversas aproximaciones que transitan entre lo histórico, lo sociocultural, lo estético, e inclusive desde sus dimensiones patrimoniales y folclóricas. Como parte de la cultura popular, nos acompaña por el costado de la historia oficial supuestamente seria. Y nos ayuda a especular sobre la forma de lo que no conocemos; por ejemplo, los extraterrestres.

PP: Muy bien, saliste dignamente. Bueno, sabemos que tienes una gran inclinación por el humor político. Así que hablemos un poco del tema: ¿Por qué es importante el humor político?

JORGE: Porque es otra forma de hacer política, de opinar, de referirse al poder político sin solemnidad, sin reverencias, desde una perspectiva crítica inusual o no-convencional que revela las incoherencias o ridiculeces que puede contener un discurso político aparentemente serio.

PP: De acuerdo. Y creo que es importante también para darle otro punto de vista a los consumidores, porque puede ser que no hayan pensado así, no se les haya ocurrido edsa idea. Es una especie de didactimos muy necesario, ¿no es cierto? Pero para ti, ¿el humor es de izquierda o de derecha? ¿De ambos o de ninguno?

JORGE: La sátira política es siempre crítica. No es neutra. Puede venir desde cualquier lado. No es patrimonio de la izquierda o la derecha. No obstante, la persona -o la publicación- que hace humor puede tener un compromiso, una postura, una posición, valores, que determinan su perspectiva… que puede ser de izquierda o derecha. En mi caso, que me “formé” bajo una dictadura, es más bien de izquierda y autocrítica.

PP: Por supuesto. Mi único problema al respecto es cuando un colega, del color político que sea, no critica los errores de las autoridades porque son de su misma ideología. Entiendo la parte emotiva, pero creo que perjudica un poco al humor, ¿no te parece? Bueno, es un tema a tratar en otro espacio. Lo dejamos pendiente. Jorge, ¿te han censurado alguna vez? ¿Has sido testigo de alguna injusta y terrible censura? ¿Te autocensuras?

JORGE: La autocensura fue un ejercicio permanente bajo dictadura que, paradójicamente, era un buen estímulo a la creatividad para eludirla y aludirla. En los años ’80 publicamos la revista “La Castaña”. Solicitamos la autorización del Ministerio del Interior para que circulara legalmente, pero nunca respondieron, así que la publicamos corriendo el riesgo. Cuando trabajamos con Eduardo de la Barra en La Tercera, algunas veces nos rechazaron dibujos por razones políticas.

PP: De total acuerdo con eso de que la autoscensura en dictaduras nos hace más creativo… Mira, una vez, durante mi serie de documentales sobre el humor, “El bufón ilustrado”, amablemente colaboraste y diste una explicación sobre los límites del humor que me encantó. ¿Puedes darla aquí de nuevo? (Aunque no sea con las mismas palabras, por supuesto).

JORGE: Ja ja… ya no me acuerdo lo que dije. Puedo decir, repitiéndome o no, que en nosotros, que tenemos la suspicacia del humor, que es una forma de mirar, el humor no tiene límites. La imaginación no tiene límites. Se nos puede ocurrir cualquier cosa, incluso lo más políticamente incorrecto. El desafío es está en la inteligencia social, en considerar el contexto en el cual se nos ocurre un chiste, por ejemplo, y (auto)permitirnos decirlo o no. Hay que ser ubicados. El público (infantil, por ejemplo) puede no ser el adecuado para ciertas ocurrencias. A veces, por graciosos, podemos tensionar una reunión social, así como podemos distenderla con una talla oportuna.

PP: Dices que los límites los ponemos nosotros mismos, ¿no? Te lo compro. Pero me pregunto, y las respresiones dictatoriales, las que ponen lo dueños de los medios, ¿las que imponen minorías fanatizadas, etc., ¿no son límites también? Seguro están dentro de tu respuesta “considerar el contexto en el cual se nos ocurre un chiste”. Podríamos, cuando tengamos más tiempo, hacer un video para profundizar más sobre esto. Y ahora para relajar un poco, ¿puedes contar alguna anécdota graciosa, curiosa o ingeniosa que hayas vivido en tu carrera en el humor?

JORGE: En los años ’80, con Rufino hicimos un libreto para un café-concert de Maitén Montenegro. Un monólogo que tenía varios cuadros. En uno de ellos Maitén era una reina mandona en un tablero de ajedrez. Para nosotros -con malicia política- la reina era la Lucía de Pinochet que lo retaba descaradamente. Poco antes del estreno Maitén nos dice que le preocupaba que el rey resultara parecido a Pinochet. No era su idea. Le dijimos que tampoco era la nuestra, pero que era un problema de quienes hacían la escenografía. El día del estreno se abren las cortinas y ahí estaba el rey: un monigote que era igual a Onofre Jarpa: ¡el ministro del interior! Y el respetable público era más bien de derecha, gente de la tele. La obra duró poco.

PP: Ja, ja, me imagino. Jorge, ¿qué te gustaría hacer dentro del humor que no hayas hecho? Quizás un tipo de humor, quizás una modalidad distinta, o cualquier proyecto nuevo para ti …

JORGE: Me ronda la idea de un libreto para un stand up comedy. Libreto. Yo nunca me subiría al escenario para ello.

PP: No te imagino en un escenario. Sin embargo, sé que si hay que hacerlo, eres capaz de hacerlo. Y para ir cerrando, ¿se te ocurre alguna pregunta que te hubiese gustado que te hiciera y no te hice? Si es así, ¿la puedes responder ahora?

JORGE: Es bueno que tengamos más preguntas que respuestas… y que queden pendientes. Por ejemplo, la relación del humor con la poesía. Desde ahí me acerqué al humor. Primero hice epigramas, poemas autoirónicos.

PP: Me encanta hacer epigramas y epitafios también. Pero en serio, es un tremendo tema ese de poesía y humor. Me encantaría hacer algo yo también al respecto. Bueno, y por último, , ¿puedes decirle unas palabras a nuestros seguidores de Humor Sapiens?

JORGE: Que el humor -aquí- no es para la risa.

PP: Espero que lo sepan, ja, ja. Bueno, querido amigo mío, llegó el momento de agradecerte infinitamennte que me hayas dedicado tu tiempo, esfuerzo y neuronas. La pasé muy bien en este vis a vis contigo. Espero que tú también lo hayas disfrutado. Te deseo mucha salud y muchos éxitos más. Un abrazo gigante.

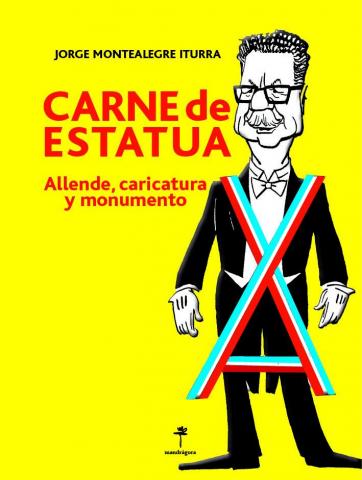

Portada - libro - CARNE DE ESTATUA - Allende, caricatura y monumento.

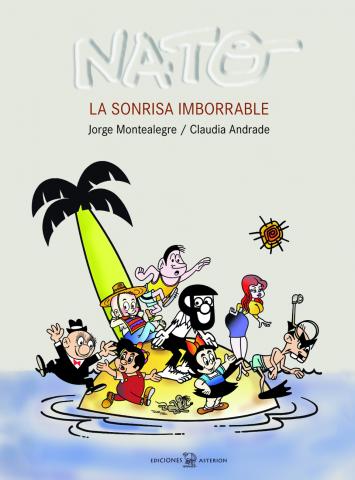

Portada - Libro - Nato.

Portada - libro - Sentido del Rumor.

Portada - libro - Von Pilsener.

Interview with Jorge Montealegre

By Pepe Pelayo

I understand humor as a human, intelligent quality

The Chilean Jorge Montealegre (1954) is a journalist, poet, essayist, researcher, cultural manager, specialist in graphic humor, director of the Humor Research and Studies Network (RIEH), Chile and creative editor and scriptwriter of graphic humor.

He worked for a long time making jokes, for example, for the humorous publications Condorito and Topaze.

He has published a few books, among them: Von Pilsener, the first character in the Chilean comic strip; Pure Chile. Humorous and (anti)patriotic satire, Prehistorieta de Chile, from rock art to the first cartoon newspaper and Sentido del Rumor. Monkeys and cuties under dictatorship.

He has been awarded countless times. He obtained the Guggenheim Scholarship (1989), which allowed him to write History of graphic humor in Chile.

But for me, in addition to being a great creator of humor and an excellent student of humor and apart from being a renowned poet and essayist (his “serious” career is very successful), he is my friend. He was the first comedian I met when I arrived in Chile. We've even done things together in humor.

For all these reasons, I am very happy to have you here “dialocating” with me in this space.

PP: Dear Jorge, introducing you I remembered the “Cacheras Nights” at your house. To clarify: you invited many friends to play cacho, as an excuse to talk a little wine together and laugh a lot. I miss those meetings. On those nights I met a few important Chilean comedians like Hervi, Gai, de la Barra and others. I hope that if you resume that tradition you will invite me again, okay?

JORGE: More than one person thought that the “cacheros nights” were a kind of orgy. They were disappointed. The ceviche that Hervi provided is unforgettable and why say the “pancake cake” that Pía made. A regular attendee, also from the field of humor, was Pancho Zañartu. Very good scriptwriter, from “Los Venegas” and other programs. Hernán Venegas was a live Venegas (illustrator of the strip “Entrelíneas”. Infaltable. Anyway… the dice and the chub were good excuses to get together and have a good time. And laugh.

PP: My Zañartu, of course! Well, after that nice memory, I begin the interrogation: did I introduce you well? Did I miss anything you would like to add? And beyond, how would you like to be remembered?

JORGE: Very generous. I am self-taught with a PhD.

PP: A self-taught person with a master's degree would be me then. Well, how did you become interested in creating, researching, and studying humor?

JORGE: When in 1981 we published -without authorization- the magazine “La Castaña”, Luis Albornoz made a section that consisted of a crowd of people from whom bubbles of dialogue and thought came out without text. In white. Since I was the literary editor, he gave me the drawings and told me that it was up to me to fill in those gaps. I came from poetry, very Parrian, so I copied some texts from Perich and dared to invent some of my own. Very soon I made them all myself, without having to copy. I became a screenwriter because the editor of the Sunday supplement of La Tercera liked this and later that company published the newspaper La Cuarta. And with the great Eduardo de la Barra as illustrator we made the “Sense of Rumor” section and a lot of other works, including the character “Palomita”. This foray into humor allowed me to meet cartoonists that I had always admired (Palomo, Hervi, Themo Lobos, Nato, the Vivanco brothers...) and I realized that they had many stories and a History that they would not write. So I started researching. And I'm still at it.

PP: I love that you continue researching with the same passion. What you do is precious and very important work. I send you (healthy or unhealthy). Now let's theorize more, what is humor for you? (I mean your definition of it and what it means to you).

JORGE: Without entering into the old and unfinished distinctions about humor, laughter, the comic (which occupied Bakhtin, Bergson, Freud and other thinkers); In a simple way, I understand humor as a human, intelligent quality that allows us to perceive and create laughable situations that provoke various emotions, some of which are expressed with an inner smile or laughter. Within humor, I have been especially interested in satire and I have tried a definition about it: I consider that satire is a critical, irreverent and burlesque representation of reality. Critical, because it expresses an opinion, generally dissatisfied, with respect to what is represented. Irreverent, because it desacralizes; It subtracts formality from situations consecrated as worthy of solemn treatment. This irreverence breaks or diminishes hierarchies (it refuses reverence) making the dialogue more horizontal: everything that is susceptible to being honored can resist a satirical gaze. That is, it can be reduced to the precarious humanity that resembles us all. Burlesque, because it detects and reveals the comic aspects contained in the situation - produced without humorous intention - and exposes them to public laughter with mordacity. Finally, satire is a representation of reality, because it is anchored in it and proposes relevant associations with real sayings or events, a perspective that includes, reveals, that percentage of ridiculousness that everything we do has.

Graphic humor – despite the frivolity or lack of seriousness that it could connote – functions as a complex sociocultural phenomenon within which various approaches can be approached that range between the historical, the sociocultural, the aesthetic, and even from its heritage dimensions. and folklore. In their variety, the graphic representations of the “Chilean people” - originally media-based - have infiltrated and installed themselves in tradition and popular culture, configuring a broad humorous iconography, which has diversified as access to the media has expanded. consumption of workers and society is increasingly more complex. The review of this iconography shows that generally the exhibition of each representative character lasts over time decontextualized from the historical and social processes that have originated the stereotypes and caricatures.

PP: You evaded your definition of humor a bit, but you enjoyed the definition of satire. Thanks for that “master class”. Now, I was going to ask you a question, but you already answered it. I'll ask you the same thing and see what you answer... If an alien arrived and, having never seen a work of graphic humor (not a caricature, nor a comic strip, nor a comic, or anything like that, and asked you "what is graphic humor? ?”, how would you define it so that I understand it?

JORGE: First I would ask you what you think of the Macians, the ETs and the aliens of graphic humor and I would try to explain to you that graphic humor – despite the frivolity or lack of seriousness that it could connote – functions as a complex sociocultural phenomenon within the which can address various approaches that range between the historical, the sociocultural, the aesthetic, and even from its heritage and folkloric dimensions. As part of popular culture, it accompanies us on the side of supposedly serious official history. And it helps us speculate about the shape of what we don't know; For example, aliens.

PP: Very good, you left with dignity. Well, we know you have a great penchant for political humor. So let's talk a little about the topic: Why is political humor important?

JORGE: Because it is another way of doing politics, of giving an opinion, of referring to political power without solemnity, without reverence, from an unusual or non-conventional critical perspective that reveals the inconsistencies or ridiculousness that an apparently serious political discourse can contain.

PP: Okay. And I think it is also important to give consumers another point of view, because it may be that they have not thought that way, that idea has not occurred to them. It's a very necessary kind of didactym, isn't it? But for you, is the humor left or right? Of both or neither?

JORGE: Political satire is always critical. It is not neutral. It can come from anywhere. It is not the heritage of the left or the right. However, the person - or the publication - that makes humor may have a commitment, a position, a position, values, that determine their perspective... which may be left or right. In my case, since I was “trained” under a dictatorship, it is rather left-wing and self-critical.

PP: Of course. My only problem in this regard is when a colleague, of whatever political color, does not criticize the errors of the authorities because they are of the same ideology. I understand the emotional part, but I think it hurts the humor a bit, don't you think? Well, it is a topic to be discussed in another space. We left it pending. Jorge, have you ever been censored? Have you witnessed any unjust and terrible censorship? Do you censor yourself?

JORGE: Self-censorship was a permanent exercise under dictatorship that, paradoxically, was a good stimulus to creativity to avoid and allude to it. In the 80s we published the magazine “La Castaña”. We requested authorization from the Ministry of the Interior for it to circulate legally, but they never responded, so we published it at our risk. When we worked with Eduardo de la Barra at La Tercera, we sometimes had drawings rejected for political reasons.

PP: I completely agree with that self-censorship in dictatorships makes us more creative… Look, once, during my series of documentaries on humor, “The Illustrated Jester,” you kindly collaborated and gave an explanation about the limits of humor that I loved. Can you give it here again? (Although not with the same words, of course).

JORGE: Ha ha… I don't remember what I said. I can say, repeating myself or not, that in us, who have the suspicion of humor, which is a way of looking, humor has no limits. Imagination has no limits. We can come up with anything, even the most politically incorrect. The challenge is in social intelligence, in considering the context in which a joke occurs to us, for example and (self)allow ourselves to say it or not. They must be located. The audience (children, for example) may not be appropriate for certain occurrences. Sometimes, by being funny, we can put stress on a social gathering, just as we can relax it with an opportune size.

PP: You say that we set the limits ourselves, right? I buy it to you. But I wonder, what about dictatorial repressions, those imposed by media owners, those imposed by fanatical minorities, etc., aren't they also limits? Surely they are within your answer “consider the context in which we come up with a joke.” We could, when we have more time, make a video to go into more detail about this. And now to relax a little, can you tell a funny, curious or witty anecdote that you have experienced in your career in comedy?

JORGE: In the '80s, Rufino and I made a libretto for a café-concert at Maitén Montenegro. A monologue that had several frames. In one of them Maitén was a bossy queen on a chess board. For us - with political malice - the queen was Pinochet's Lucía who shamelessly challenged him. Shortly before the premiere, Maitén tells us that he was worried that the king would turn out to be similar to Pinochet. It wasn't his idea. We told him that it wasn't ours either, but that it was a problem of those who made the scenery. On the day of the premiere, the curtains opened and there was the king: a puppet who looked like Onofre Jarpa: the minister of the interior! And the respectable audience was more right-wing, TV people. The work did not last long.

PP: Ha ha, I imagine. Jorge, what would you like to do within the humor that you haven't done? Maybe a type of humor, maybe a different modality, or any new project for you...

JORGE: I'm thinking about the idea of a script for a stand up comedy. Libretto. I would never get on stage for it.

PP: I can't imagine you on stage. However, I know that if it has to be done, you are capable of doing it. And to close, can you think of any questions that you would have liked me to ask you but I didn't? If so, can you answer it now?

JORGE: It's good that we have more questions than answers... and that they remain pending. For example, the relationship of humor with poetry. From there I approached humor. First I made epigrams, self-ironic poems.

PP: I love making epigrams and epitaphs too. But seriously, it's a tremendous topic of poetry and humor. I would love to do something about it too. Well, and finally, can you say a few words to our Humor Sapiens followers?

JORGE: That humor -here- is not for laughter.

PP: I hope they know, ha ha. Well, my dear friend, the time has come to thank you infinitely for having dedicated your time, effort and neurons to me. I had a great time in this “dialogue” with you. I hope you enjoyed it too. I wish you good health and many more successes. A giant hug.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)