“¿Por qué lo llaman amor cuando quieren decir sexo?”. Esta es una frase muy conocida que expresa bien la gran confusión que existe hoy entre esos dos conceptos. Suele ser atribuida a Groucho Marx y en España dio título a una película en 1992: una comedia dirigida por Manuel Gómez Pereira y protagonizada por Verónica Forqué, Rosa María Sardá y Jorge Sanz. Pues bien, también en nuestros días se confunde con facilidad cierto tipo de humor con el odio puro y duro. Y la responsable de esta confusión es la sátira mal entendida.

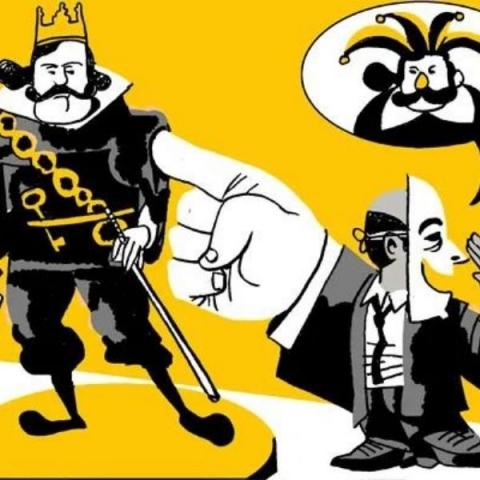

Como dice el caricaturista, escritor e investigador gallego Siro López, dentro del humor, entendido coloquialmente como todo lo que intenta hacer reír o sonreír, podemos distinguir tres grandes géneros: la comicidad, la sátira y el humorismo. La comicidad se dirige solo a la inteligencia y busca la risa, sin ningún otro fin útil o moral. La sátira se dirige también a la inteligencia y busca igualmente la risa, pero no como un fin en sí mismo, sino para usarla como arma contra alguien o algo. Consiste, en definitiva, en la ridiculización por medio de la burla. Por último, el humorismo se dirige tanto a la inteligencia como al sentimiento, emociona a la vez que divierte y tiene como respuesta la sonrisa comprensiva o solidaria. Puede ser de dos tipos: benévolo, si intenta evitar la comicidad y no reír a tontas y a locas, sino comprender, disculpar y sonreír; y sarcástico o negro, cuando se afana en evitar la tragedia, para lo que caricaturiza la tristeza y ríe por no llorar.

Yo, como Siro (lo ha confesado en público más de una vez), prefiero la comicidad y el humorismo a la sátira. Por mi propia naturaleza, por mi forma de ser. Y la ironía. Prefiero también la ironía a la sátira. Siempre he sido muy irónico y muy poco satírico. La ironía cómica y la ironía humorística, digo. Porque hay una ironía cómica, otra humorística y otra satírica. La satírica me tira menos porque nunca me ha gustado demasiado la burla. Coincido con el gran Miguel Gila cuando decía: “… detesto la burla. No tiene nada que ver con el humor. Desgraciadamente, muchos no encuentran la diferencia. El humor embellece. La burla afea. Y el mundo es lo suficientemente feo como para que lo queramos afear más”. Lo mismo dice el filósofo André Comte-Sponville, aunque él llama a la burla ironía (en realidad, se está refiriendo al sarcasmo, a la ironía mordaz y cruel que suele servir de base a la sátira): “La ironía [la burla, el sarcasmo, la sátira, insisto] hiere, el humor cura. La ironía puede matar, el humor ayuda a vivir. La ironía quiere dominar, el humor libera. La ironía es despiadada, el humor es misericordioso. La ironía es humillante, el humor es humildad”.

Esto no quiere decir que no valore y disfrute también la sátira… a veces. Si no es exactamente “la defensa de la ofensa de vivir”, como afirmó Césare Pavese de la literatura –yo diría que eso lo es más bien la comicidad y sobre todo el humorismo–, la sátira sí que puede ser una defensa-ofensa del débil frente al fuerte, de la víctima frente al verdugo, del pueblo frente al poder. Un arma incruenta, aunque temible. Con razón alguien dijo que “Inglaterra no tuvo revoluciones porque tuvo la sátira”, aunque no es cierto del todo, ya que sí hubo una revolución inglesa, en la segunda mitad del siglo XVII, que terminó con el derrocamiento del rey Jacobo II y la coronación de Guillermo de Orange (Guillermo III), después de la breve experiencia de la República de Oliver Cromwell.

Pero el poder revolucionario de la sátira es relativo. Tiene una evidente función catártica, pero la venganza del satírico se pierde en el aire. Además, es un arma de doble filo, porque, si nos permite desahogarnos, también nos deja desasosegados, con el regusto amargo de la hostilidad. En este sentido, la comicidad también se revela pronto como una mala solución. Nos ayuda a evadirnos de la realidad por un tiempo, pero cuando despertamos de la anestesia del sentimiento en que nos sume, la realidad aún está ahí, como el dinosaurio del microrrelato de Augusto Monterroso. Nos volvemos a dar de bruces con ella, y sin tener verdaderas armas o estrategias para evitar que nos hiera mortalmente. El humorismo, en cambio, sí nos da esas estrategias: el descubrimiento de que la realidad es poliédrica, de que tiene muchas caras, y la posibilidad de elegir entre ellas la más amable, la menos amenazante. Por eso es “la defensa de la ofensa de vivir” y nos salva muchas veces de la desesperación. El humorismo nos ayuda a dar sentido a acontecimientos que de otra manera nos aplastarían. Es un antídoto contra la mala leche que va comiéndonos el espíritu. La sátira, no. Al revés, suele ser un potenciador de esa mala leche. Frente a la revolución de la sátira, el humorismo puede parecer reformista, pero es más revolucionario de lo que creemos. No revoluciona el mundo, pero sí nos revoluciona a nosotros mismos porque nos hace ver la realidad desde un punto de vista nuevo. Y cuando cambiamos nosotros, cambia el mundo.

La sátira no tiene que ser justa –no es una crítica constructiva– y de hecho, con frecuencia es injusta. Pensemos, por ejemplo, en ese famosísimo soneto de Francisco de Quevedo contra su competidor Luis de Góngora que comienza “Érase un hombre a una nariz pegado”. Por supuesto que Góngora no tenía una nariz mayor que todo su cuerpo. Es una exageración. Pero a nadie se le ocurriría sancionar a Quevedo por escribir eso o prohibir la circulación del poema. Estamos ante un ataque satírico que todos entendemos que no tiene por qué circunscribirse a la realidad ni ser justo. En el caso de la viñeta de humor, comprendemos esto fácilmente cuando la concebimos, como hace Llorenç Gomis, como “una noticia imaginaria en función de comentario”. Si la “noticia” de la que nos reímos es “imaginaria”, difícilmente podemos pedirle al humorista que se ajuste a la realidad ni que sea justo. Es una de las licencias de la sátira.

Pero una cosa es que la sátira no tenga que ser justa y otra que resulte tan sectaria y llena de odio que respire injusticia por todos sus poros, además de resultar aburrida por reiterativa y falta de ingenio. Decía Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro, el gran caricaturista portugués, que la sátira política debe ser oposición a los gobiernos y también a las oposiciones; es decir, reírse de todo y si acaso de todos, pero desde luego no solo de unos cuantos, siempre los mismos –los que no piensan como yo–, máxime si esta sátira tan sectaria va acompañada, como va cada vez más, por la pretensión totalitaria de que nadie pueda hacer sátira contra mí y mis amigos, los que piensan como yo. Amigos, por cierto, que en seguida pasan a ser enemigos porque ya sabemos que para el pensamiento totalitario toda discrepancia, por mínima que sea, es considerada alta traición.

Nunca me ha gustado demasiado la sátira –ya lo he dicho–, pero últimamente me gusta aún menos, por esto que digo, hasta el punto de que he dejado de seguir revistas y programas de televisión que en otro tiempo me divertían. Sus dardos satíricos me aburren e irritan cada vez más y no porque yo haya cambiado de ideas o me haya vuelto más intolerante, sino porque la sátira legítima está siendo sustituida cada vez más por un discurso de odio y sectarismo disfrazado de ella o de humor negro. Un buen ejemplo lo tenemos en los chistes recurrentes que algunos en España llevan haciendo desde hace más de treinta años sobre Irene Villa, una mujer con una capacidad de autosuperación admirable que en 1991, cuando era solo una niña de doce años, fue víctima de un gravísimo atentado terrorista de ETA en el que perdió las dos piernas, y su madre –que conducía el coche en el que viajaban, y al que habían puesto una bomba adosada–, un brazo y una pierna. Hoy es una periodista, psicóloga y escritora con unos fuertes valores humanos que, por lo que se ve, chocan frontalmente con los antivalores de quienes insisten en hacer esos chistes sobre ella. Burlarse de quienes sufren no es humor; es una canallada. Entre el verdugo y quien se ríe del sufrimiento de la víctima no hay ninguna diferencia moral. ¿Por qué lo llaman humor cuando quieren decir odio?

Oh, humor, oh, humor | Why do they call it humor when they mean hate?

By Félix Caballero

“Why do they call it love when they mean sex?” This is a well-known phrase that well expresses the great confusion that exists today between these two concepts. It is usually attributed to Groucho Marx and in Spain it gave the title to a film in 1992: a comedy directed by Manuel Gómez Pereira and starring Verónica Forqué, Rosa María Sardá and Jorge Sanz. Well, nowadays too, certain types of humor are easily confused with pure and simple hatred. And the person responsible for this confusion is poorly understood satire.

As the Galician caricaturist, writer and researcher Siro López says, within humor, colloquially understood as everything that tries to make people laugh or smile, we can distinguish three major genres: comedy, satire and humor. Comedy is directed only at intelligence and seeks laughter, without any other useful or moral purpose. Satire is also aimed at intelligence and also seeks laughter, but not as an end in itself, but to use it as a weapon against someone or something. It consists, in short, of ridicule through mockery. Finally, humor is directed at both intelligence and feeling, it excites as well as amuses and is responded to by a sympathetic or supportive smile. It can be of two types: benevolent, if you try to avoid comedy and not laugh foolishly and madly, but rather understand, apologize and smile; and sarcastic or black, when he strives to avoid tragedy, for which he caricatures sadness and laughs so as not to cry.

I, like Siro (he has confessed it in public more than once), prefer comedy and humor to satire. By my own nature, by my way of being. And the irony. I also prefer irony to satire. I have always been very ironic and very unsatirical. Comic irony and humorous irony, I say. Because there is a comic irony, another humorous and another satirical. The satirical one appeals less to me because I have never really liked mockery. I agree with the great Miguel Gila when he said: “… I hate mockery. It has nothing to do with humor. Unfortunately, many do not see the difference. Humor beautifies. The ugly mockery. And the world is ugly enough that we want to make it uglier.” The philosopher André Comte-Sponville says the same thing, although he calls mockery irony (in reality, he is referring to sarcasm, the biting and cruel irony that usually serves as the basis of satire): “Irony [mockery, sarcasm, satire, I insist] hurts, humor heals. Irony can kill, humor helps you live. Irony wants to dominate, humor liberates. Irony is ruthless, humor is merciful. Irony is humiliating, humor is humility.”

This doesn't mean that I don't also value and enjoy satire... sometimes. If it is not exactly “the defense of the offense of living”, as Césare Pavese stated about literature – I would say that this is rather what comedy and especially humor is –, satire can indeed be a defense-offense of the weak against the strong, of the victim against the executioner, of the people against power. A bloodless, yet fearsome, weapon. No wonder someone said that "England did not have revolutions because it had satire", although it is not entirely true, since there was an English revolution, in the second half of the 17th century, which ended with the overthrow of King James II and the coronation of William of Orange (William III), after the brief experience of Oliver Cromwell's Republic.

But the revolutionary power of satire is relative. It has an obvious cathartic function, but the satirist's revenge is lost in the air. Furthermore, it is a double-edged sword, because, if it allows us to vent, it also leaves us uneasy, with the bitter aftertaste of hostility. In this sense, comedy also soon reveals itself as a bad solution. It helps us escape from reality for a while, but when we wake up from the anesthesia of the feeling in which it plunges us, reality is still there, like the dinosaur in Augusto Monterroso's short story. We come face to face with it again, and without having any real weapons or strategies to prevent it from mortally wounding us. Humor, on the other hand, does give us these strategies: the discovery that reality is multifaceted, that it has many faces, and the possibility of choosing among them the most friendly, the least threatening. That is why it is “the defense of the offense of living” and it often saves us from despair. Humor helps us make sense of events that would otherwise crush us. It is an antidote to the bad temper that is eating away at our spirit. Satire, no. On the contrary, it is usually an enhancer of that bad temper. Faced with the revolution of satire, humor may seem reformist, but it is more revolutionary than we believe. It does not revolutionize the world, but it does revolutionize ourselves because it makes us see reality from a new point of view. And when we change, the world changes.

Satire does not have to be fair – it is not constructive criticism – and in fact, it is often unfair. Let us think, for example, of that very famous sonnet by Francisco de Quevedo against his competitor Luis de Góngora that begins “Once upon a time there was a man stuck to a nose.” Of course Góngora did not have a nose larger than his entire body. It's an exaggeration. But no one would think of sanctioning Quevedo for writing that or prohibiting the circulation of the poem. We are facing a satirical attack that we all understand does not have to be limited to reality or be fair. In the case of the humorous vignette, we easily understand this when we conceive it, as Llorenç Gomis does, as “an imaginary news item based on commentary.” If the “news” we laugh at is “imaginary”, we can hardly ask the comedian to adjust to reality or be fair. It is one of the licenses of satire.

But it is one thing that satire does not have to be fair and another that it is so sectarian and full of hatred that it breathes injustice from every pore, in addition to being boring due to repetitiveness and lack of ingenuity. Raphael Bordallo Pinheiro, the great Portuguese caricaturist, said that political satire must be opposition to governments and also oppositions; That is to say, laugh at everything and perhaps at everyone, but certainly not just at a few, always the same ones - those who don't think like me -, especially if this highly sectarian satire is accompanied, as it is increasingly, by totalitarian claim that no one can make satire against me and my friends, those who think like me. Friends, by the way, who immediately become enemies because we already know that for totalitarian thinking any discrepancy, no matter how minor, is considered high treason.

I have never liked satire very much – I have already said it – but lately I like it even less, because of what I say, to the point that I have stopped following magazines and television programs that once entertained me. Their satirical darts bore and irritate me more and more and not because I have changed my ideas or have become more intolerant, but because legitimate satire is being replaced more and more by hate speech and sectarianism disguised as it or by black humor. . We have a good example in the recurring jokes that some in Spain have been making for more than thirty years about Irene Villa, a woman with an admirable capacity for self-improvement who in 1991, when she was just a twelve-year-old girl, was the victim of a very serious terrorist attack by ETA in which he lost both legs, and his mother - who was driving the car in which they were traveling, and to which they had attached a bomb -, an arm and a leg. Today she is a journalist, psychologist and writer with strong human values that, apparently, clash head-on with the anti-values of those who insist on making those jokes about her. Making fun of those who suffer is not humor; It's a scoundrel. There is no moral difference between the executioner and the one who laughs at the victim's suffering. Why do they call it humor when they mean hate?

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)