En el Boletín Humor Sapiens de octubre publiqué un artículo sobre la figura del payaso, al que pretendía rendir un sentido homenaje. Retomo ahora el asunto centrándome en la figura del payaso en el cine clásico de Hollywood, especialmente en la trasposición de la tradicional pareja circense del carablanca o clown y el augusto o nariz roja. La figura del clown fue creada por Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837), considerado el primer payaso moderno; la del augusto, por Tom Belling (1843-1900).

La comedia está presente en el cine desde sus mismos inicios. La primera película de ficción pertenecía ya a este género: L’arroseur arrosé (El regador regado, en España y Latinoamérica), rodada por los hermanos Lumiere en Francia en 1895, el mismo año que se da como inaugural del cine. La historia es tan simple como la broma que un chico le gasta a un jardinero pisando la goma cuando este riega un jardín. En el momento en el que el jardinero inspecciona la manguera para ver qué ocurre, el muchacho levanta el pie y el hombre acaba empapado, empezando la persecución para darle su escarmiento al niño. Simple, directo y efectivo. Uno de los primeros gags de la historia del celuloide, que ponía ya los cimientos del slapstick (la comedia física), que marcaría todo el posterior cine cómico mudo y parte del sonoro (las persecuciones, las guerras de tartas, etc.).

No es extraño, pues, que el primer cine cómico se nutriera de actores procedentes del mundo del circo y del vodevil. El primero que quedó para la historia no surgió, curiosamente en EEUU, a pesar de que tengamos asociado cine cómico mudo con Hollywood, sino en Francia, donde, bien mirado, no debe sorprender esta aparición, por ese origen francés del cine y de la comedia que acabamos de reseñar. Este cómico no fue otro que Max Linder (1893-1925), quien, por cierto, probó fortuna en EEUU, pero sin demasiada suerte, por lo que no tardó en regresar a su país. El personaje de Linder era un dandy, vestido siempre de etiqueta, con guantes, bastón y su imponente sombrero de copa. Su primer gran éxito fue Les débuts d’un patineur (Max patinador[1], 1907), donde ataviado con su habitual gala, sombrero incluido, trataba de aprender a patinar sobre hielo. A diferencia de lo que se había hecho hasta entonces, principalmente persecuciones, caídas o peleas, Linder introduce un nuevo rumbo al humor, con comedias de enredo o situaciones comprometidas donde el actor trata de no perder la compostura pese a sus habituales fracasos… y siempre impecablemente vestido.

Linder fue el maestro de Charles Chaplin (1889-1977), según confesó este mismo. Por cierto que, aunque Charlot era un vagabundo, no dejaba de tener, en la intención, e incluso en el vestuario –con un bombín en vez de un sombrero de copa–, algo del exquisito caballero de Linder, ya que se esforzaba por comportarse con los modales y dignidad de un gentleman. Chaplin formó parte de la troupe de payasos que desembarcaron en el cine mudo y trabajaron en la famosa “factoría” de Mack Sennett. Cinco nombres han pasado a la historia: Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Fatty Arbuckle y Harry Langdon.

Pero en el cine cómico de Hollywood enseguida se impuso el modelo del dúo de payasos: el clown o carablanca y el augusto o nariz roja, en duelo permanente. Algunos los han interpretado mal como el listo y el tonto. Mejor es hablar del serio –el formal, el sensato– y del travieso –el bromista, el juguetón–. El clown es autoritario y distinguido. Lleva la cara pintada de blanco y representa la ley, el orden, el mundo adulto, la represión. El augusto es extravagante, absurdo, pícaro, liante, torpe, sorprendente, entusiasta, provocador. Suele lucir una característica nariz roja y representa la libertad y la anarquía, el mundo infantil. Nunca es un imbécil. Es astuto, listo, de entendimiento vivo y despierto, y acaba por vencer siempre todas las dificultades y por ganarle la partida al clown.

Laurel y Hardy

La primera y mejor pareja de payasos de Hollywood fueron Stan Laurel (1890-1965) y Oliver Hardy (1892-1957), llamados el Gordo y el Flaco en España y en Latinoamérica. Oliver encarnaba al clown y Laurel al augusto, con muchas licencias, por supuesto, propias del cambio de lenguaje y de medio que suponía pasar del circo al cine. El iniciador de la idea del dúo fue Leo McCarey, uno de los grandes directores de la comedia clásica de Hollywood. Desde 1927 a 1951 interpretaron más de 70 cortos mudos y sonoros y 23 largometrajes, entre ellos County Hospital (Hospital provincial, 1932, de James Parrott), The music box (Haciendo de las suyas, 1932, de James Parrott) Sons of the desert (Compañeros de juerga, 1933, de William A. Seiter) o The flying deuces (Locos del aire, 1939, de Eddie Sutherland).

La aparición del sonoro conllevó la desaparición de muchos actores de la época silente; Laurel y Hardy, sin embargo, tuvieron una transición relativamente fácil hacia el cine parlante. El acento inglés de Laurel y el acento estadounidense sureño de Hardy dieron una nueva dimensión a sus personajes. La pareja usó los diálogos para enfatizar, más que para desplazar, su humor de tipo visual. Según Eric de Bont, un holandés que dirige desde hace décadas una escuela de payasos en las islas Baleares –primero en Ibiza y ahora en Menorca–, Laurel y Hardy representan como nadie el espíritu del payaso, que no es otro que el del niño adulto, el del inocente perpetuo.

Los hermanos Marx

Laurel y Hardy tuvieron una gran competencia en los hermanos Marx, que hicieron 13 películas entre 1929 y 1949, entre ellas Duck soup (Sopa de ganso, 1933, de Leo McCarey) y A night at the opera (Una noche en la ópera, 1935, de Sam Wood). Pero los Marx, más que payasos, eran bufones. No entraré aquí a profundizar en las diferencias entre ambos conceptos. Baste con decir que del payaso –o con el payaso (importante matiz que no podemos explicar ahora)– se ríen los demás, mientras que el bufón se ríe él de los otros. Veámoslo comparando una frase de Groucho Marx con una de Woody Allen, otro de los grandes payasos del cine. Groucho dice: “Nunca olvido una cara, pero en su caso voy a hacer una excepción”. Woody, por el contrario, se lamenta: “La gente me olvida incluso cuando me está dando la mano”.

Decía que los hermanos Marx son más bufones que payasos, y solo podrían, si acaso, ser concebidos como un grupo de payasos en sus cinco primeras películas, en las que actúa también Zeppo. Este podría, efectivamente, encarnar al clown, mientras que Groucho funcionaría como augusto y Chico y Harpo, como contraugustos, que vienen a amplíar los gags del augusto. Zeppo era el menor de los hermanos, y, según se dice, el más divertido de todos –capaz, incluso, de sustituir a Groucho en algunas representaciones–; sin embargo, aparecía siempre como un personaje recto, romántico y poco cómico. Tras dejar la interpretación, se dedicó al mundo de la mecánica, creando diversos inventos.

Abbott y Costello

Pero volvamos al clown y al augusto. El relevo del Gordo y el Flaco lo tomaron en Hollywood Abbott y Costello. Bud Abbott (1895-1974) representaba al clown y Lou Costello (1906-1959) al augusto. Hicieron 36 películas entre 1940 y 1956, además de triunfar también en el teatro, la radio y la televisión. Formaron el equipo cómico más popular en EEUU durante los años 40. También en Latinoamérica; sin embargo, en España no tuvieron mucho éxito. Entre sus largometrajes más célebres figuran Hold that ghost (Agárrame ese fantasma, 1941, de Arthur Lubin), Pardon my sarong (Dos caraduras con suerte, 1942, de Erle C. Kenton), The time of their lives (El fantasma huye, 1946, de Charles Barton), Abbott y Costello meet Frankenstein (Abbott y Costello contra los fantasmas, 1948, de Charles Barton) y Abbott y Costello meet the invisible man (Abbott y Costello contra el hombre invisible, 1951, de Charles Lamont).

Crosby y Hope

Abbott y Costello tuvieron una réplica en Bing Crosby (1903-1977) y Bob Hope (1903-2003), quienes, también con un esquema más o menos de clown-augusto, filmaron siete películas entre 1940 y 1962, las famosas Road to…, todas ellas secuelas de Road to Singapore (Ruta de Singapur, 1940, de Victor Schertzinger). Por cierto que en una de ellas, Road to Bali (Camino a Bali, 1952, de Hal Walker), hicieron un cameo Dean Martin y Jerry Lewis, quienes actualizarían la ecuación de la pareja (y también la de Abbott y Costello). Durante la preproducción de la que iba a ser su octavo filme juntos, en 1977, Crosby murió de un ataque al corazón.

Martin y Lewis

Aunque nacidos como pareja en el contexto de lo que más tarde se conocería como stand-up comedy, Dean Martin (1917-1995) y Jerry Lewis (1926-2017) se convirtieron enseguida en herederos de la larga tradición del augusto y contraaugusto. Martin y Lewis rodaron juntos 16 películas entre 1949 y 1966, con títulos memorables como My friend Irma (Mi amiga Irma, 1949, de George Marshall), Artists and models (Cómicos en París, 1955, de Frank Tashlin) y Hollywood or Bust (Loco por Anita, 1956, de Frank Tashlin). La Anita en cuestión era la exuberante Anita Ekberg, a la que Federico Fellini inmortalizó en La dolce vita (1960).

Mientras que la figura impertinente y buscavidas de Martin no sufriría ningún cambio durante los 16 filmes que filmaron juntos, el caricato de Lewis cada vez fue adquiriendo un mayor protagonismo. Su histrionismo adoptaba el sentido de la parodia, de la crítica, del reflejo distorsionado de un mundo decadente al que había que hacer reír para que saliera de su burbuja impermeable. De hecho, este desequilibrio fue la causa principal de la ruptura del dúo, que, como suele acontecer en estos casos, pasó muchos años distanciado, incluso sin hablarse.

Lewis realizaría después una prestigiosa carrera en solitario como director y actor de comedia, con títulos como The bellboy (El botones, 1960), The nutty professor (El profesor chiflado, 1963) o Which way to the front (¿Dónde está el frente?, 1970).

Matthau y Lemmon

Otra pareja memorable fue la constituida por Walter Matthau (1920-2000) y Jack Lemmon (1925-2001). Por supuesto, el modelo original del circo clown-augusto estaba ya muy diluido y es difícil establecer quién era aquí el uno y quién el otro. En realidad, los dos tenían algo de carablanca y de nariz roja. Matthau era el liante, el tramposo, el que metía al pobre Lemmon en todo tipo de berenjenales, mientras que su amigo era el prudente, el pesimista. En cualquier caso, el contraste –y, por lo tanto, el duelo– de caracteres resultaba evidente y sus diálogos y discusiones acabaron convirtiéndose en legendarios.

Mattau y Lemmon protagonizaron ocho películas juntos entre 1966 y 1998, aunque, por supuesto, durante esos más de 30 años los dos interpretaron por su lado otros muchos filmes. Sus nombres como pareja cómica han quedado ligados fundamentalmente al de Billy Wilder, que los dirigió en tres de sus cintas más famosas: The fortune cookie (En bandeja de plata, 1966), por la que Matthau consiguó un Óscar al mejor actor de reparto; The front page (Primera plana, 1974) y Buddy Buddy (Aquí un amigo, 1981). Pero Howard Deutch los dirigió también en tres títulos: Grumpy old men (Dos viejos gruñones, 1993), Grumpier old men (Dos viejos gruñones 2 o Discordias a la carta, 1995) y The odd couple (La extraña pareja, otra vez, 1998). Sus otras dos películas juntos fueron The odd couple (La extraña pareja, 1968), de Gene Saks, y Out to sea (Por rumbas y a lo loco, 1997), dirigida por Martha Cooligde. Además, Lemmon –que en esa ocasión no se puso delante de las cámaras– dirigió a Matthau en Kotch (Señor Kotcher, 1971).

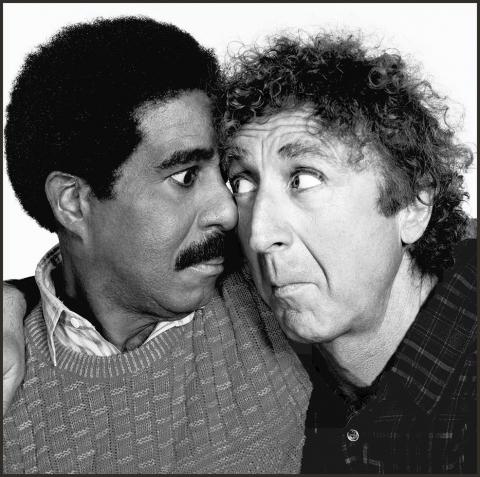

Wilder y Pryor

Cerramos este particular recuento de duelos de payasos en el cine clásico de Hollywood con Richard Pryor (1940-2005) y Gene Wilder (1933-1916), una de las parejas cómicas interraciales más famosas de la historia del cine, un tipo de encuadre que más adelante se repetiría muchas veces, como en la saga Lethal weapon (Arma letal, 1987, 1989, 1992 y 1998), protagonizada por Mel Gibson y Danny Glover

Pryor es considerado uno de los mejores exponentes de la stand up comedy estadounidense de todos los tiempos. Comedy Central y Rolling Stone lo auparon al número uno de sus listas correspondientes.

Por su parte, Wilder tuvo una notable carrera como actor y director. Como intérprete, destacó en Young Frankenstein (El jovencito Frankenstein, 1974, de Mel Brooks). Como director, consiguió un gran éxito con The woman in red (La mujer de rojo, 1984), en la que se dirigió a sí mismo acompañado por Kelly LeBrock.

Pryor y Wilder rodaron cuatro películas juntos entre 1976 y 1991: Silver streak (El expreso de Chicago, 1976, de Arthur Hiller), Stir crazy (Locos de remate, 1981, de Sidney Poiter), See no evil, hear no evil (No me chilles, que no te veo, 1989, de Arthur Hiller) y Another you (No me mientas que te creo, 1991, de Maurice Phillips). Estaba previsto que filmaran una quinta, Trading places (Entre pillos anda el juego, 1983, de John Landis), pero un incidente protagonizado por Pryor –en uno de sus arrebatos de locura inducidos por el consumo de drogas se pegó fuego a sí mismo– los separó del proyecto. Al final, la cinta fue interpretada por Eddie Murphy y Dan Aykroyd.

***

El modelo del duelo o dúo de payasos heredado del circo ha dado mucho juego en el cine de Hollywood, con todas las modificaciones y adaptaciones que se puedan imaginar, produciendo un buen número parejas cómicas a partir de Laurel y Hardy. Fue tanta la popularidad que alcanzaron algunas que el Gordo y el Flaco (1966) y Abbott y Costello (1967) llegaron a tener su propia serie de dibujos animados en la televisión –ambas a cargo de Hanna-Barbera–, y Martin y Lewis, de cómic (1952).

[1] Este título en castellano y todos los demás a partir de él que aparecen en el artículo se corresponden con los que recibieron las películas en España.

Payasos: clown y augusto

Laurel y Hardy

Los Hermanos Marx

Abott y Costello.

Crosby and Hope

Martin and Lewis

Matthau and Lemmon

Wilder and Pryor

Great clown duels in classic Hollywood cinema

Bay Félix Caballero

In the October Humor Sapiens newsletter I published an article about the figure of the clown, to which I intended to pay a heartfelt tribute. I now return to the matter focusing on the figure of the clown in classic Hollywood cinema, especially in the transposition of the traditional circus couple of the whiteface or clown and the august or red nose. The figure of the clown was created by Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837), considered the first modern clown; that of the Augustus, by Tom Belling (1843-1900).

Comedy has been present in cinema since its very beginnings. The first fiction film already belonged to this genre: L'arroseur arrosé (The Watered Irrigator, in Spain and Latin America), filmed by the Lumiere brothers in France in 1895, the same year that the cinema was inaugurated. The story is as simple as the joke that a boy plays on a gardener by stepping on the rubber when he waters a garden. At the moment the gardener inspects the hose to see what is happening, the boy raises his foot and the man ends up soaked, beginning the chase to teach the boy his lesson. Simple, direct and effective. One of the first gags in the history of celluloid, which already laid the foundations of slapstick (physical comedy), which would mark all subsequent silent comic films and part of the sound films (the chases, the cake wars, etc.).

It is not surprising, then, that the first comedy films were nourished by actors from the world of circus and vaudeville. The first one that remained in history did not emerge, curiously, in the United States, despite the fact that we have silent comic films associated with Hollywood, but in France, where, looking closely, this appearance should not be surprising, due to the French origin of cinema and comedy that we just reviewed. This comedian was none other than Max Linder (1893-1925), who, by the way, tried his luck in the US, but without much luck, so he soon returned to his country. Linder's character was a dandy, always dressed in evening clothes, with gloves, a cane and his imposing top hat. His first great success was Les débuts d’un patineur (Max skater[1], 1907), where dressed in his usual finery, hat included, he tried to learn how to ice skate. Unlike what had been done until then, mainly chases, falls or fights, Linder introduces a new direction to humor, with sitcoms or compromised situations where the actor tries not to lose his composure despite his usual failures... and always impeccably dressed.

Linder was the teacher of Charles Chaplin (1889-1977), according to what Chaplin himself confessed. Certainly, although Charlot was a vagabond, he still had, in his intention, and even in his costume - with a bowler hat instead of a top hat - something of Linder's exquisite gentleman, as he strove to behave with the manners and dignity of a gentleman. Chaplin was part of the troupe of clowns that landed in silent films and worked in Mack Sennett's famous “factory.” Five names have gone down in history: Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Fatty Arbuckle and Harry Langdon.

But in Hollywood comedy cinema the model of the clown duo quickly took hold: the clown or white face and the august or red nose, in permanent duel. Some have misinterpreted them as the smart one and the fool. It is better to talk about the serious one – the formal one, the sensible one – and the mischievous one – the joker, the playful one. The clown is authoritarian and distinguished. His face is painted white and he represents law, order, the adult world, and repression. The august is extravagant, absurd, mischievous, confusing, clumsy, surprising, enthusiastic, provocative. He usually sports a characteristic red nose and represents freedom and anarchy, the child's world. He's never a jerk. He is cunning, clever, with a lively and alert understanding, and always ends up overcoming all difficulties and winning the game against the clown.

Laurel and Hardy

The first and best couple of Hollywood clowns were Stan Laurel (1890-1965) and Oliver Hardy (1892-1957), called Fat and Skinny in Spain and Latin America. Oliver played the clown and Laurel played the august, with many licenses, of course, typical of the change in language and medium that went from the circus to the cinema. The initiator of the idea of the duo was Leo McCarey, one of the great directors of classic Hollywood comedy. From 1927 to 1951 they performed more than 70 silent and sound shorts and 23 feature films, among them County Hospital (Provincial Hospital, 1932, by James Parrott), The music box (Doing His Thing, 1932, by James Parrott) and Sons of the Desert. (Partners of the party, 1933, by William A. Seiter) or The flying deuces (Locos del aire, 1939, by Eddie Sutherland).

The appearance of sound led to the disappearance of many actors from the silent era; Laurel and Hardy, however, had a relatively easy transition into talking pictures. Laurel's English accent and Hardy's Southern American accent gave a new dimension to their characters. The couple used dialogue to emphasize, rather than displace, their visual humor. According to Eric de Bont, a Dutchman who has run a clown school in the Balearic Islands for decades – first in Ibiza and now in Menorca –, Laurel and Hardy represent the spirit of the clown like no other, which is none other than that of the adult child. , that of the perpetual innocent.

The Marx Brothers

Laurel and Hardy had great competition in the Marx Brothers, who made 13 films between 1929 and 1949, including Leo McCarey's Duck Soup (1933) and A Night at the Opera (1935). , by Sam Wood). But the Marxes, more than clowns, were jesters. I will not go into the differences between the two concepts here. Suffice it to say that others laugh at the clown – or with the clown (an important nuance that we cannot explain now) – while the jester laughs at others. Let's see it by comparing a phrase from Groucho Marx with one from Woody Allen, another of the great clowns of cinema. Groucho says, “I never forget a face, but in your case I'm going to make an exception.” Woody, on the other hand, laments: “People forget me even when they are shaking my hand.”

He said that the Marx Brothers are more jesters than clowns, and could only, if at all, be conceived as a group of clowns in their first five films, in which Zeppo also stars. This could, effectively, embody the clown, while Groucho would function as Augustus and Chico and Harpo, as contraugustos, who come to expand the Augustus's gags. Zeppo was the youngest of the brothers, and, it is said, the funniest of all – even capable of replacing Groucho in some performances; However, he always appeared as a straight, romantic and not very comical character. After leaving acting, he dedicated himself to the world of mechanics, creating various inventions.

Abbott and Costello

But let's go back to the clown and the august. The baton of Fatty and Skinny was taken over in Hollywood by Abbott and Costello. Bud Abbott (1895-1974) represented the clown and Lou Costello (1906-1959) the august. They made 36 films between 1940 and 1956, in addition to also succeeding in theater, radio and television. They formed the most popular comedy team in the US during the 40s. Also in Latin America; However, in Spain they were not very successful. Among his most famous feature films are Hold that ghost (1941, by Arthur Lubin), Pardon my sarong (Two cheeks with luck, 1942, by Erle C. Kenton), The time of their lives (The ghost flees, 1946 , by Charles Barton), Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein (Abbott and Costello against the ghosts, 1948, by Charles Barton) and Abbott and Costello meet the invisible man (Abbott and Costello against the invisible man, 1951, by Charles Lamont).

Crosby and Hope

Abbott and Costello had a replica in Bing Crosby (1903-1977) and Bob Hope (1903-2003), who, also with a more or less clown-august scheme, filmed seven films between 1940 and 1962, the famous Road to… , all sequels to Road to Singapore (1940, by Victor Schertzinger). By the way, in one of them, Road to Bali (1952, by Hal Walker), Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis made a cameo, who would update the couple's equation (and also that of Abbott and Costello). During pre-production of what was to be their eighth film together, in 1977, Crosby died of a heart attack.

Martin and Lewis

Although born as a couple in the context of what would later be known as stand-up comedy, Dean Martin (1917-1995) and Jerry Lewis (1926-2017) quickly became heirs of the long tradition of august and counter-august. Martin and Lewis made 16 films together between 1949 and 1966, with memorable titles such as My friend Irma (1949, by George Marshall), Artists and models (Comedians in Paris, 1955, by Frank Tashlin) and Hollywood or Bust ( Crazy for Anita, 1956, by Frank Tashlin). The Anita in question was the exuberant Anita Ekberg, whom Federico Fellini immortalized in La dolce vita (1960).

While the impertinent and hustler figure of Martin would not undergo any change during the 16 films they filmed together, Lewis's caricature increasingly took on greater prominence. His histrionics adopted the sense of parody, of criticism, of the distorted reflection of a decadent world that had to be made to laugh in order for it to come out of its impermeable bubble. In fact, this imbalance was the main cause of the breakup of the duo, who, as usually happens in these cases, spent many years estranged, even without speaking.

Lewis would later pursue a prestigious solo career as a comedy director and actor, with titles such as The bellboy (1960), The nutty professor (1963) and Which way to the front (Where is the front? , 1970).

Matthau and Lemmon

Another memorable couple was that of Walter Matthau (1920-2000) and Jack Lemmon (1925-2001). Of course, the original model of the clown-august circus was already very diluted and it is difficult to establish who was here one and who was the other. In reality, they were both somewhat white-faced and red-nosed. Matthau was the troublemaker, the cheater, the one who got poor Lemmon into all kinds of trouble, while his friend was the prudent one, the pessimist. In any case, the contrast – and, therefore, the duel – of characters was evident and their dialogues and discussions ended up becoming legendary.

Mattau and Lemmon starred in eight films together between 1966 and 1998, although, of course, during those more than 30 years the two starred in many other films on their own. Their names as a comic couple have been fundamentally linked to that of Billy Wilder, who directed them in three of his most famous films: The fortune cookie (On a silver platter, 1966), for which Matthau won an Oscar for best supporting actor; The front page (First page, 1974) and Buddy Buddy (Here a friend, 1981). But Howard Deutch also directed them in three titles: Grumpy old men (1993), Grumpier old men (1995) and The odd couple (1998). ). Their other two films together were The odd couple (1968), by Gene Saks, and Out to sea (Por rumbas y a lo loco, 1997), directed by Martha Cooligde. Furthermore, Lemmon – who did not appear in front of the cameras on that occasion – directed Matthau in Kotch (Mr. Kotcher, 1971).

Wilder and Pryor

We close this particular account of clown duels in classic Hollywood cinema with Richard Pryor (1940-2005) and Gene Wilder (1933-1916), one of the most famous interracial comic couples in the history of cinema, a type of framing that Later it would be repeated many times, as in the Lethal Weapon saga (1987, 1989, 1992 and 1998), starring Mel Gibson and Danny Glover.

Pryor is considered one of the best exponents of American stand up comedy of all time. Comedy Central and Rolling Stone lifted it to number one on their corresponding lists.

For his part, Wilder had a notable career as an actor and director. As a performer, he stood out in Young Frankenstein (1974, by Mel Brooks). As a director, he achieved great success with The Woman in Red (1984), in which he directed himself accompanied by Kelly LeBrock.

Pryor and Wilder made four films together between 1976 and 1991: Silver streak (Chicago Express, 1976, by Arthur Hiller), Stir crazy (Locos de remate, 1981, by Sidney Poiter), See no evil, hear no evil (No scream at me, I don't see you, 1989, by Arthur Hiller) and Another you (Don't lie to me, I believe you, 1991, by Maurice Phillips). They were scheduled to film a fifth, Trading Places (1983, by John Landis), but an incident involving Pryor – in one of his outbursts of madness induced by drug consumption, he set himself on fire – separated them from the project. In the end, the film was performed by Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd.

***

The model of the duel or clown duo inherited from the circus has been widely used in Hollywood cinema, with all the modifications and adaptations that can be imagined, producing a good number of comic couples based on Laurel and Hardy. Some of them were so popular that Fat and Skinny (1966) and Abbott and Costello (1967) even had their own cartoon series on television – both by Hanna-Barbera – and Martin and Lewis, comic (1952).

[1] This title in Spanish and all the others from it that appear in the article correspond to those that the films received in Spain.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)