¿Es posible casar el humor y la política? ¿Pueden ser compañeros de vida (o, mejor, de juegos)? De entrada, parece que no. Son dos campos, supuestamente, muy alejados, incluso antitéticos. Pocas cosas se nos podrían ocurrir más distantes del humor que la política. Y esto, por dos razones. La primera, por la visión imperante (y bastante equivocada) de que la política es una cosa muy seria y el humor, por el contrario, algo frívolo. La segunda, por la percepción (más ajustada a la realidad) de la política como antipática, aburrida y a veces hasta repugnante, verdaderamente en las antípodas del humor. Sin embargo, la respuesta a la pregunta tiene que ser afirmativa. No en vano, han existido (y existen) en ciertos lugares y momentos algunos buenos ejemplos de esto. No muchos, pero sí buenos. La mayoría –todo hay que decirlo–, fuera de España, sobre todo en el mundo anglosajón –especialmente en los EEUU–, aunque también unos cuantos en nuestro país. El objetivo de este artículo no es reflexionar sobre cómo se pueden casar ambos mundos, sino, más bien, recopilar algunos de esos ejemplos a los que me refería; es decir, dejar constancia, con casos concretos, de que, por extraño que les parezca a algunos, humor y política (o política y humor) pueden ir a veces de la mano. Vamos al lío.

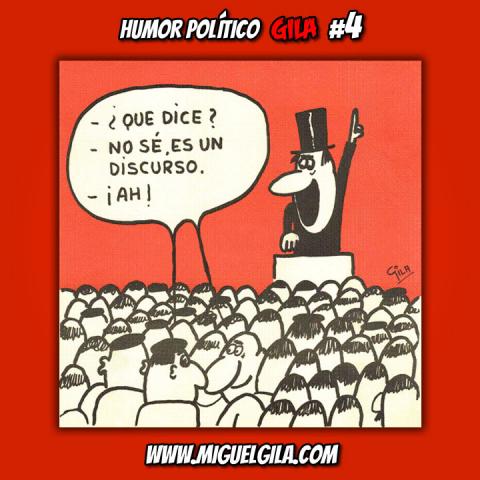

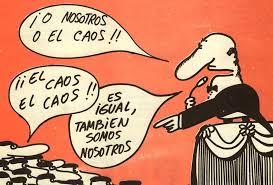

Cuando hablo aquí de humor político no me refiero al uso del humor por el pueblo o los periodistas (sus supuestos representantes) como un arma para defenderse de los políticos (o tal vez atacarlos), es decir, a la sátira política, presente en la prensa desde sus inicios (cuando dejó de haber censura previa, claro). Esa sátira tan temida por todos los Gobiernos, especialmente por los autocráticos. Hablo, por el contrario, del humor de los propios políticos, para atacar a sus adversarios en el Parlamento o en los medios de comunicación o (mejor aún, en mi opinión) para defenderse de sí mismos y defendernos a todos nosotros de ellos.

Un ejemplo de la capacidad de los políticos de autoparodiarse y reírse de sí mismos lo encontramos, en el mundo anglosajón, en la cena anual de la Asociación de Corresponsales de la Casa Blanca, que se viene celebrando desde 1921 (hace ya más de cien años) y a la que tradicionalmente asisten el presidente y el vicepresidente de los EEUU. Desde 1983 (hace ya cuarenta años), el anfitrión destacado es un comediante y la cena ha adoptado la forma de una crítica humorística del presidente y su administración. Lo más interesante es que el presidente suele autoparodiarse. Pero, desgraciadamente, no se trata de un verdadero ejercicio de reconocimiento humilde de los propios límites (que en esto consiste en buena medida el humor aplicado a uno mismo), sino más bien de una práctica más o menos frívola para diversión de la prensa. Digamos que se ha convertido en una especie de ritual puramente frívolo que no tiene que ver con el verdadero uso del humor para hacer una política más humilde, democrática y cercana al pueblo. De hecho, después de la cena de 2007, el columnista del New York Time Frank Rich escribió que el evento se había convertido en una cristalización de los fracasos de la prensa en la era posterior al 11-S (por los atentados de las Torres Gemelas) porque ilustraba con qué facilidad una Casa Blanca impulsada por la propaganda podía incorporar a los medios de comunicación de Washington en sus programas.

Sin duda, uno de los presidentes estadounidenses que más juego ha dado en la cena ha sido Barak Obama. En 2016, en su última intervención, el acto comenzó con un vídeo en el que se hacía recuento de los momentos más embarazosos registrados durante sus dos mandatos. En la grabación, aparecía cometiendo equivocaciones en público como no poder deletrear una palabra o tirando objetos en medio de sus discursos. Pero lo mejor fue el final, en el que urgió a los asistentes a aceptar su invitación a la red Linkedin y remató con dos palabras: “Obama out” (“Obama fuera”), antes de tirar el micrófono al suelo e irse del atril. Por el contrario, Donald Trump (que amenaza ahora con volver a ser presidente) no fue a ninguna de las tres cenas que tuvieron lugar durante su mandato. Las vetó expresamente. Como se sabe, su relación con la prensa es peculiar.

Otro buen ejemplo (este, quizás, más interesante) de la disposición de algunos políticos a reírse de sí mismos y a que el público se ría con ellos es el late show estadounidense Saturday Night Live. Desde su primer año de emisión, en 1975 (hace 50 años) han sido muchos los políticos que han aceptado participar en gags, dando ejemplo de la integración del uso del humor televisivo en la comunicación política norteamericana. En aquellos primeros tiempos candidatos a la presidencia como Ralph Nader (1977), senadores como Julian Bond (1977) y alcaldes como Ed Koch (1983) se prestaron ya a hacer comedia con el programa. Luego vendrían otras personalidades políticas como Jesse Jackson, Al Gore, John McCain o Barak Obama, aunque quizás el episodio más popular hasta la fecha de unión de comedia y política lo protagonizaron las actrices Tina Fey y Amy Poehler dando vida a Sarah Palin y Hillary Clinton en un sketch emitido en plena carrera presidencial de 2008 en el que fueron acompañadas por las verdaderas candidatas a la Casa Blanca.

En España esto es mucho más difícil de ver, aunque en los últimos años por algunos programas televisivos como El Hormiguero (Antena 3) han desfilado Pedro Sánchez y Mariano Rajoy siendo presidentes del Gobierno en funciones y candidatos a la reelección. Algunos políticos hasta se han creído su papel y han intentado rentabilizarlo, pensando que su popularidad aumentaría y con ella sus votos. El caso más claro es el del expresidente de la Comunidad Autónoma de Cantabria, Miguel Ángel Revilla, al que últimamente le ha salido un competidor en alcalde de la ciudad gallega de Vigo, Abel Caballero. En 2022 se enfrentaron en el programa, al que ya habían acudido más de una vez por separado, para medir su popularidad, pues los dos presumían de ser el político más popular de España. Al final, el duelo fue mucho menos divertido de lo esperado y se quedó más bien en una conversación de barra de bar en la que se respiraba mucho ego.

En EEUU también es normal que la ficción de comedia acoja a representantes del mundo de la política. Tenemos dos buenos ejemplos en Al Gore riéndose de su obstinado ecologismo en la comedia de situación 30 Rock, creada por Tina Fey (“Perdonadme, tengo que irme; estoy oyendo llorar a una ballena”) y en John McCain, Joe Biden y Michelle Obama en Parks and Recreation, la sitcom política de Amy Poehler.

En España esto sigue siendo muy raro, pero ya hay casos. El exvicepresidente del Gobierno Alfonso Guerra apareció en la serie 7 vidas en un papel de profesor universitario con el que se autoparodiaba y el expresidente Mariano Rajoy, entonces ministro de Educación y Cultura, hizo de sí mismo en una aparición fugaz en un capítulo de Jacinto Durante representante. Claro que los momentos más desternillantes que nos dejó Rajoy fueron de humor involuntario, como cuando dijo en una entrevista televisiva que “los que nos dedicamos a la política somos sentimientos y tenemos seres humanos”. Humor involuntario o simplemente dislexia. En cualquier caso, hay que reconocer que protagonizó muchas y buenas muestras del uso inteligente de la ironía en sus intervenciones en el Congreso de los Diputados.

Otro capítulo interesante de la unión entre humor y política lo protagonizan aquellos cómicos que han entrado en política. El caso más famoso es, probablemente, el del actual presidente de Ucrania, Volodimir Zelensky, que cimentó su popularidad como comediante en la televisión de su país y al que finalmente aupó a la presidencia su papel en una serie en la que, premonitoriamente, interpretaba a un humilde profesor que se convertía por casualidad en el presidente de Ucrania, después de que se viralizara un vídeo en el que despotricaba contra la corrupción.

Otro buen ejemplo de comediante metido a la política lo tenemos en nuestra propia Latinoamérica: Jimmy Morales, quien se convirtió en presidente de Guatemala en 2016 (hasta 2020), encarnando la antipolítica y frustración de sus paisanos provocadas por las corruptelas en el Gobierno del general Otto Pérez Molina. Morales conquistó su popularidad con el programa de televisión Moralejas, junto a su hermano Sammy.

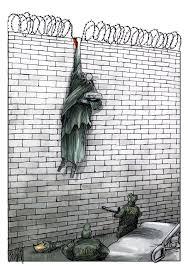

Claro que ni Morales ni Zelensky han tenido muchos motivos para reír durante sus mandatos, aunque el segundo sí para intentar hacer reír a sus conciudadanos. Reír por no llorar, evidentemente, para mantener la moral alta en la guerra que Ucrania viene padeciendo con Rusia.

En conclusión, los políticos en general y particularmente en España aún tienen pendiente descubrir las posibilidades que les ofrece en su propio beneficio (y seguro que también en el de los votantes) el uso del humor en la comunicación política. Pero quizás deberían empezar por utilizarlo en sus intercambios dialécticos en los parlamentos y en sus comparecencias de prensa. Todos saldríamos ganando, porque la política sería mucho menos aburrida y tal vez también mucho menos mezquina. En los últimos tiempos se ha convertido en un espectáculo y no precisamente cómico, aunque con frecuencia sí grotesco. Pero no es un espectáculo cómico lo que demando yo aquí, sino un uso inteligente del humor para hacer de la política algo más divertido, sí, pero especialmente más humano y verdadero.

Oh, humor, oh humor | Humor and politics

By Félix Caballero

Is it possible to marry humor and politics? Can they be life (or, better, play) companions? At first glance, it seems not. They are two fields, supposedly, very distant, even antithetical. Few things could occur to us that are more distant from humor than politics. And this for two reasons. The first, due to the prevailing (and quite wrong) view that politics is a very serious thing and humor, on the contrary, is something frivolous. The second, due to the perception (more adjusted to reality) of politics as unfriendly, boring and sometimes even repugnant, truly at the antipodes of humor. However, the answer to the question has to be affirmative. Not in vain, some good examples of this have existed (and exist) in certain places and times. Not many, but good. The majority - it must be said - outside Spain, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world - especially in the US -, although also a few in our country. The objective of this article is not to reflect on how both worlds can be married, but, rather, to compile some of those examples to which I referred; That is, to record, with specific cases, that, as strange as it may seem to some, humor and politics (or politics and humor) can sometimes go hand in hand. Let's go to trouble.

When I talk about political humor here, I am not referring to the use of humor by the people or journalists (their supposed representatives) as a weapon to defend themselves against politicians (or perhaps attack them), that is, political satire, present in the press since its beginnings (when there was no longer prior censorship, of course). That satire so feared by all governments, especially autocratic ones. I speak, on the contrary, of the humor of the politicians themselves, to attack their adversaries in Parliament or in the media or (even better, in my opinion) to defend themselves and all of us against them.

An example of the ability of politicians to parody and laugh at themselves is found, in the Anglo-Saxon world, at the annual dinner of the White House Correspondents' Association, which has been held since 1921 (more than a hundred years ago). ) and which is traditionally attended by the president and vice president of the United States. Since 1983 (forty years now), the featured host is a comedian and the dinner has taken the form of a humorous critique of the president and his administration. The most interesting thing is that the president often parodies himself. But, unfortunately, it is not a true exercise in humble recognition of one's own limits (which is largely what humor applied to oneself consists of), but rather a more or less frivolous practice for the amusement of the press. Let's say that it has become a kind of purely frivolous ritual that has nothing to do with the true use of humor to make politics more humble, democratic and closer to the people. In fact, after the 2007 dinner, New York Time columnist Frank Rich wrote that the event had become a crystallization of the failures of the press in the post-9/11 era. ) because it illustrated how easily a propaganda-driven White House could incorporate the Washington media into its programs.

Without a doubt, one of the American presidents who has played the most at the dinner has been Barak Obama. In 2016, in his last intervention, the event began with a video recounting the most embarrassing moments recorded during his two terms in office. In the recording, he appeared making mistakes in public such as not being able to spell a word or throwing objects in the middle of his speeches. But the best was the end, in which he urged the audience to accept his invitation to the Linkedin network and finished with two words: “Obama out,” before throwing the microphone to the ground and leaving the lectern. . In contrast, Donald Trump (who now threatens to become president again) did not attend any of the three dinners that took place during his term. He expressly vetoed them. As is known, his relationship with the press is peculiar.

Another good example (this one, perhaps, more interesting) of the willingness of some politicians to laugh at themselves and for the public to laugh with them is the American late show Saturday Night Live. Since its first year of broadcast, in 1975 (50 years ago), many politicians have agreed to participate in gags, setting an example of the integration of the use of television humor in North American political communication. In those early days, presidential candidates like Ralph Nader (1977), senators like Julian Bond (1977) and mayors like Ed Koch (1983) already volunteered to do comedy with the program. Then came other political personalities such as Jesse Jackson, Al Gore, John McCain or Barak Obama, although perhaps the most popular episode to date of the union of comedy and politics starred actresses Tina Fey and Amy Poehler playing Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton. in a sketch broadcast in the middle of the 2008 presidential race in which they were accompanied by the real candidates for the White House.

In Spain this is much more difficult to see, although in recent years Pedro Sánchez and Mariano Rajoy have appeared on some television programs such as El Hormiguero (Antena 3) as acting presidents of the Government and candidates for re-election. Some politicians have even believed in their role and have tried to make it profitable, thinking that their popularity would increase and with it their votes. The clearest case is that of the former president of the Autonomous Community of Cantabria, Miguel Ángel Revilla, who has recently had a competitor for mayor of the Galician city of Vigo, Abel Caballero. In 2022 they faced each other on the program, which they had already attended more than once separately, to measure their popularity, since the two boasted of being the most popular politician in Spain. In the end, the duel was much less fun than expected and remained more of a bar conversation in which a lot of ego was in the air.

In the US it is also normal for comedy fiction to welcome representatives from the world of politics. We have two good examples in Al Gore laughing at his stubborn environmentalism in the sitcom 30 Rock, created by Tina Fey (“Excuse me, I have to go; I'm hearing a whale cry”) and in John McCain, Joe Biden and Michelle Obama in Parks and Recreation, Amy Poehler's political sitcom.

In Spain this is still very rare, but there are already cases. The former vice president of the Government Alfonso Guerra appeared in the series 7 lives in a role of a university professor with which he parodied himself and the former president Mariano Rajoy, then Minister of Education and Culture, played himself in a fleeting appearance in an episode of Jacinto Durante representative. Of course, the most hilarious moments that Rajoy left us were of involuntary humor, like when he said in a television interview that “those of us who dedicate ourselves to politics have feelings and we have human beings.” Involuntary humor or simply dyslexia. In any case, it must be recognized that he carried out many good examples of the intelligent use of irony in his interventions in the Congress of Deputies.

Another interesting chapter in the union between humor and politics is carried out by those comedians who have entered politics. The most famous case is probably that of the current president of Ukraine, Volodimir Zelensky, who cemented his popularity as a comedian on television in his country and who was finally promoted to the presidency for his role in a series in which, presciently, he played to a humble professor who by chance became the president of Ukraine, after a video in which he ranted against corruption went viral.

We have another good example of a comedian involved in politics in our own Latin America: Jimmy Morales, who became president of Guatemala in 2016 (until 2020), embodying the anti-politics and frustration of his countrymen caused by the corruption in the general's government. Otto Pérez Molina. Morales gained popularity with the television program Moralejas, along with his brother Sammy.

Of course, neither Morales nor Zelensky have had many reasons to laugh during their mandates, although the latter has had to try to make his fellow citizens laugh. Laugh to avoid crying, obviously, to keep morale high in the war that Ukraine has been suffering with Russia.

In conclusion, politicians in general and particularly in Spain have yet to discover the possibilities that the use of humor in political communication offers them for their own benefit (and surely also for that of voters). But perhaps they should start by using it in their dialectical exchanges in parliaments and in their press appearances. We would all benefit, because politics would be much less boring and perhaps also much less petty. In recent times it has become a spectacle, and not exactly a comic one, although it is often grotesque. But what I demand here is not a comic show, but rather an intelligent use of humor to make politics more fun, yes, but especially more human and true.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)