El humor como arma elegante, aguda y penetrante

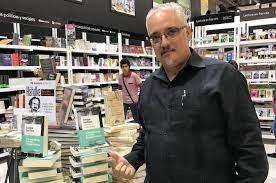

Podría presentar a este colega copiando lo siguiente de Wikipedia: “Enrique del Risco Arrocha conocido como Enrisco (La Habana, 9 de noviembre de 1967), es un escritor y humorista cubano. Licenciado de Historia de Cuba por la Universidad de La Habana, en 1990, y doctorado en Literatura Latinoamericana en la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU) en 2005. Reside en West New York, Nueva Jersey, desde 1997. Ocupa un puesto de lecturer en la propia Universidad de Nueva York. Logró el XX Premio Unicaja de Novela Fernando Quiñones en 2018”.

Pero también puedo presentarlo como alguien que admiro por cómo escribe y por lo que escribe, ya sea para teatro en la “belle époque” del humor en los años 80 o por sus artículos publicados (aún no he podido leer su premiada novela). Lo sigo en su blog y tuve la oportunidad de compartir con él en Nueva York después de años sin verlo (desde finales de la década mencionada), y de verdad que lo considero un grande del humor cubano y una buena persona. Por lo que me pesa no haber desarrollado más una profunda amistad con él, aunque no fue culpa de ninguno de los dos, sólo de los caminos de la vida.

Como esperaba, fue un honor y un placer desarrollar con él este diáloco.

PP: ¿Tienes consciencia de que eres un referente en el humor cubano? ¿Que muchas personas y sobre todo los humoristas del boom de los años 80 te tienen como un grande? ¿De que estás en la historia del humor cubano por tus libros, por el “San Zumbado”, etc.? Me imagino que sí, obvio. Entonces la pregunta es ¿cómo te sientes con eso? Es una responsabilidad, ¿no? ¿Has tratado de convencerte de que no es así? En fin, ¿cómo has asumido esa realidad?

ENRISCO: Un creador debe tomarse en serio su trabajo pero no a sí mismo. Y si a lo que se dedica es a hacer humor pues con mucha más razón debe evitar esas responsabilidades como la de ser referencia de nadie. Bastante difícil es no decepcionar al público, estar a la altura de lo que puedan esperar de ti. Creo que si algo he aportado es a ayudar que temas que se tomaban con una gravedad aplastante como la historia cubana o la política, en un país con décadas de dictadura, pudieran verse desde una perspectiva humorística. Mientras en Cuba lo político era tabú y las alusiones eran muy elípticas en el exilio se le tomaba con un tono soberanamente serio. Cuando empecé a hacer humor -primero en Cuba y luego en el exilio con la columna del periódico digital Cubaencuentro- lo que se hacía como humor político era principalmente propaganda disfrazada de chiste. Muchos humoristas muy buenos le huían a lo político no por miedo sino porque les parecía que eso rebajaba la calidad de lo que hacían. Si algún mérito tuve fue demostrar una vez más -como habían hecho otros humoristas cubanos en el pasado y pienso en primer lugar en el caricaturista Eduardo Abela- que la política era un tema tan bueno para hacer humor con él como cualquier otro. No es mérito exclusivamente mío pero creo que fui de los que lo hice con mayor insistencia.

Después de todo hacer humor es tomar distancia de las cosas, una distancia que te permita ver su lado ridículo, porque no hay nada en este mundo que no tenga un costado ridículo. Burlarte de todo y no tomar en serio ni siquiera tus propias conclusiones sino también reírte de ellas. El humorista -cuando es consecuente- es el crítico más radical que existe porque se ríe de todo, empezando por sí mismo. Y es que el humor está en el extremo contrario de lo sagrado. Necesitamos la sacralidad para darle consistencia a nuestras vidas. Normalmente la gente busca lo sagrado en la religión, la política, las ideologías pero también en otras cosas como las artes, la belleza, el sexo o el deporte, algo que los empuje a una variante de lo sublime, porque lo sublime es algo que necesitamos de una manera o de otra. El humor por su parte es uno de los mejores instrumentos que se hayan inventado para poner a prueba lo sagrado, para corregir sus excesos. De ahí que a los sistemas absolutistas y totalitarios, que quieren investirse a sí mismos con un manto sagrado, el humor les resulte tan incómodo.

PP: Tienes razón, un creador no debe tomarse en serio a sí mismo. Pero lo quieras o no, eres un referente para muchos. También es cierto que el humor desacraliza y yo agregaría que desdramatiza, como matiz de desacralizar.

Y ahora paso rápido a otra pregunta. Sin dudas, el humor político, o por lo menos el relacionado con Cuba, da la impresión de que te interesa mucho, ¿no? Y lo que has creado en esos campos sabes que ha trascendido. ¿Te gustaría incursionar en otros tipos de humor aparte de lo que ya has hecho? ¿En el fondo de ti hay algo en el humor que nunca has experimentado y que quisieras hacer o lograr? ¿Te gustaría innovar, desafiarte tú mismo en un nuevo estilo, en una nueva modalidad, u otros contenidos? Son varias preguntas, pero contéstalas en una solo respuesta.

ENRISCO: Nunca he sido un profesional del humor. Casi siempre he escrito de lo que he querido cuando he querido. En la época en que crecí -en los años setenta-se respiraba, comía y cagaba política. Y por política quiero decir esa suerte de religión que era el castrismo en sus primeras décadas. En la calle, la casa, la televisión, el cine, la escuela. El tiempo se medía en años de Revolución, todo parecía tener sentido solo gracias a la política. Por eso he usado el humor como un mecanismo de desintoxicación luego de estar toda mi infancia y adolescencia expuesto a esos dogmas. Bien empleado, el humor es uno de los mejores antídotos que se han inventado contra la intoxicación por dogma. Esto te va a parecer un chiste, pero he terminado descubriendo que no me gusta la política. La política de verdad, la que se practica en los países democráticos con partidos con diferentes programas etc., me deja bastante indiferente. He descubierto que lo que no soporto es que me restrinjan la libertad o que no me respeten la inteligencia. Por eso practico el humor como una manera de confrontar la vergüenza diaria de que tu país lleve sesenta años bajo una tiranía, una cantidad de tiempo que más que política parece geológica. Pero precisamente porque esa situación en lo esencial no ha variado durante tanto tiempo se me va haciendo cada vez más difícil no repetirme al escribir sobre Cuba.

Me he preguntado si puedo hacer otra cosa que no sea humor político y quizás por eso llevo tres mundiales de fútbol consecutivos haciendo reseñas humorísticas de cada partido que veo, que son la casi totalidad de los 64 partidos que se juegan en cada mundial, y publicándolas en mi blog a medida que las escribo. Así de paso me permito jugar con un marco de referencia más amplio del que uso para hacer chistes con la política cubana y dándole algún sentido al hecho de que cada cuatro años me clavo frente al televisor un mes para ver tres y hasta cuatro partidos diarios, como si fuera un trabajo. También llevo años escribiendo una columna humorística para un periódico de Nueva York sobre la historia de la presencia latina en la ciudad desde su fundación hasta la fecha. Es un trabajo muy grato porque la historia y Nueva York son dos temas que me interesan muchísimo.

Pienso que, más que la política en sí, lo que me interesan son los tabúes sociales, cualesquiera que estos sean. Que si hubiera crecido en Arabia Saudita me burlaría de las restricciones religiosas y el machismo. No me interesa trabajar con los temas que se consideran usualmente cómicos como las suegras o la crítica de costumbres más o menos inofensivas. Cada sociedad, por liberal que se crea, engendra sus propios tabúes y contra esos tabúes es que encuentro, en lo personal, sentido y emoción escribir. Por ejemplo, hace tiempo planeo escribir un libro de fábulas sobre la corrección política, el nuevo gran tabú generado por la sociedad norteamericana, en la que vivo hace más de dos décadas, y que cada día amenaza con recortar más espacios de libertad que es el aire en el que respira cualquier humorista. Porque si algún empeño especial le veo al humor es pelear por proteger y ampliar la libertad de expresión y contra las restricciones de todo tipo: religiosas, morales, lógicas y hasta lingüísticas. Pero no para destruirlas -porque el humor por sí solo es incapaz de destruir nada- sino para hacerlas menos asfixiantes de lo que son. No por gusto uno de los más grandes humoristas de este país, Dave Chapelle, dedica últimamente todos sus monólogos más que al racismo, como hacía al comienzo de su carrera, a fustigar la corrección política porque, evidentemente, la ve más peligrosa hasta que el propio racismo.

PP: Mi pregunta iba más dirigida a si te gustaría escribir para radio, para TV, para cine, o escribirle a un actor, o hacer humor infantil, o humor en los comerciales, o crear chistes, o abordar temas nuevos para ti, etc.. En fin, ¿harías algo que nunca hayas hecho?

ENRISCO: En realidad menos comerciales he hecho de todo: radio (con El programa de Ramón); cine con Daniel Díaz Torres y también guiones de cortometrajes que nunca se filmaron. Por otra parte escribí una zarzuela (aunque yo le veo más posibilidades como musical que como zarzuela) con Paquito D’Rivera y Alexis Romay: “Cecilio Valdés, el Rey de La Habana” que tiene mucho humor. Alguna vez hice humor para televisión con Americatevé de Miami y hasta escribí una obra de teatro infantil, “El rey cocinero”, que estrenó un grupo teatral en La Habana en los 90s. También le he escrito textos a actores y grupos de teatro que todavía los reponen a cada rato. O escribí una historia de Cuba en ficción a cuatro manos con Francisco García González: Leve Historia de Cuba se llama. Y escribí, por encargo, una serie de biografías de próceres latinoamericanos dirigidas a los niños. Pero serias. Soy bastante curioso ante todo lo que me proponen pero al final me siento más cómodo escribiendo libros, a solas y de lo que quiera.

PP: ¡Pues te hice la pregunta por gusto! Disculpa, es que desconocía lo que me cuentas. Te felicito. Con más razón me siento orgulloso de dialocar contigo y de no haberme equivocado en ubicarte en el “Olimpo del Humor cubano”. Claro, te había dicho “algo que nunca has hecho”.

Bueno, paso a otra pregunta que se relaciona: ¿aceptarías el Premio Nacional de Humorismo en Cuba si te lo otorgasen este año?

ENRISCO: No. Y menos en un año en que se ha abierto la temporada de caza contra los humoristas del patio. Se vería, y con razón, como falta de solidaridad con mis colegas a los que ahora se les está persiguiendo desde las instituciones estatales y en Cuba todos los premios nacionales o los concede el Estado o al menos este da su visto bueno. Además, si oficialmente en Cuba yo no existo ¿por qué iban a darme un premio? ¿Cómo una muestra de tolerancia? Llevo casi 25 años fuera de mi país denunciando esa dictadura. ¿Por qué me darían un premio? ¿Para demostrar que el Estado cubano no solo tolera sino que premia a sus críticos? ¿Qué sentido tendría aceptarlo? Lo que hago viene con el precio de no aspirar a ningún premio cubano porque si no ¿de qué estamos hablando? ¿Premiarme a mí por lo mismo que castigan a los cubanos de la isla? ¿Aceptar un premio en un país en que la gente no tiene acceso a internet y no pueden ver, entre tantas cosas muchísimo mejores, lo que yo hago? ¿Esto es serio? ¿Hay una cámara escondida?

Y si van a conceder el Premio Nacional de Humorismo en Cuba que empiecen por el Pible, por Ramón Fernández Larrea o por ti que empezaron antes que yo y tienen una carrera bastante notoria dentro de Cuba. Respondan ustedes la pregunta y luego me cuentan.

PP: Ante todo, gracias por mencionar mi nombre en esos supuestos candidatos a premio. Pero te hice la pregunta casi sabiendo de antemano tu respuesta, un poco para meter el dedo en llaga, porque he escuchado a varios colegas hablando del asunto y unos piensan lo mismo que tú, pero otros alegan que siguen siendo cubanos y cubano es el humor que hacen, aunque vivan en otro país y por ello hay que tenerlos en cuenta para esos premios. Es como la famosa y recurrente polémica de si los artistas deben ir o no a Cuba a ofrecer su arte.

Ahora te cambio algo de tema. Mira, en la música humorística siempre los cubanos hemos tenido tradición, porque nunca han dejado de aparecer buenos compositores e intérpretes aislados. El humor gráfico tuvo su boom con el Dedeté, su prestigio y sus innumerables premios internacionales, más el apoyo del Museo del Humor y las Bienales de San Antonio y después el Melaíto; sin embargo, nadie puede afirmar que hubo un fenómeno masivo dentro del humor gráfico. Pero en los años 80 sucedió algo extraño en el humor escénico: de repente aparecieron muchísimos comediantes, guionistas, etc., y por todo el país. En Cuba siempre hubo grandes humoristas escénicos, tanto en teatro, como en TV, radio y hasta cine, pero eran figuras. Sin embargo, en los años 80 se abrió el abanico y surgieron muchos colegas. ¿Aquello fue un “Movimiento” para ti? ¿Por qué crees que sucedió eso, más aún siendo todos artistas aficionados?

ENRISCO: Sin duda fue un movimiento, de los más importantes y de los más subvalorados en la historia cultural de Cuba en las últimas décadas, como casi siempre ocurre con el humor. El humor es como la puta del pueblo: todo el mundo la busca pero nadie le da valor. O si prefieres una comparación más elegante el humor es como el aire o como el agua que la gente no le da mucho valor pero tampoco puede vivir si ellos. Nadie habla de eso pero en lo que insisten en llamarle Quinquenio Gris -que abarcó en realidad toda la década del setenta que fue la más cerrada y represiva de la historia cubana- el humor fue una de las manifestaciones más afectadas. En los setenta estuvieron prohibidos desde el rock hasta la mayoría de los baladistas en español pero a los humoristas les estaba prohibido reírse de la realidad que los rodeaba. Como todo estaba en manos del Estado, desde el transporte hasta las cafeterías, burlarse del sabor de las croquetas era cuestionar la capacidad del Estado para hacerlas. Era la época en que el principal programa humorístico era uno que se burlaba de la antigua república. Humoristas como Zumbado o Virulo se hicieron famosos a finales de esa década por tener el atrevimiento mayúsculo de burlarse de las croquetas y los taxis. (El caso de Zumbado es complicado porque sus textos más conocidos son artículos de prensa que escribió a finales de los sesenta pero habrían quedado en el olvido sin los montajes que le hizo después Carlos Ruiz de la Tejera o la antología que le publicaron a Zumbado en 1978). En los ochenta apareció una generación a la que esos límites le venían muy estrechos. Y que se dio cuenta que el humor que nos atraía venía de otra parte: de Argentina como Les Luthiers, de Inglaterra como Monty Python o de los Estados Unidos como Woody Allen, los hermanos Zucker o Mel Brooks. Gente -como la Seña del Humor de Matanzas que fundaste tú mismo- que se dio cuenta del vacío que había y comenzó a rellenarlo en espacios alternativos como festivales universitarios o peñas. No por casualidad varios de aquellos primeros grupos llevaban por nombre juegos con la palabra “peña”: la Seña, la Leña, la Piña y hasta la Pena del humor. O sea, ese movimiento floreció en los espacios menos controlados por un sistema (político) que despreciaba el humor y al mismo tiempo sospechaba de su capacidad subversiva. Porque el humor, y no me canso de insistir en ello, es subversivo por naturaleza. Eso sí, una subversión juguetona que no pretende cambiar el mundo sino que le basta con hacer reír.

En esa época todos éramos aficionados, o sea, estábamos menos contaminados por la inercia del sistema pero al mismo casi todos teníamos preparación universitaria, habíamos estudiado diferentes disciplinas y en muchos casos traíamos la riqueza de esas disciplinas al campo del humor: ingenieros, filólogos, arquitectos, historiadores del arte, psicólogos. Yo mismo era historiador. Y empezamos a atraer a un público cada vez más amplio, un público por lo general educado que estaba harto de la dieta blanda de humor que nos estaban dando por televisión. No es casual lo mucho que demoró este movimiento en asaltar los medios de difusión masiva, en establecerse en ellos. Primero con una emisora provincial de radio con El programa de Ramón y luego, bastante más tarde, la televisión, con el programa “Sabadazo”. Pero ese movimiento ya llega a la televisión de manera muy controlada, pasada por agua. Nada que ver con lo que ocurría en el teatro. Porque aquel humor sofisticadísimo y crítico que se hizo en el teatro en el ochenta cuando por fin llega a la televisión lo hace en los moldes tradicionales del humor costumbrista, el teatro bufo etc.

El movimiento humorístico de los ochenta fue aficionado en parte porque el humor es algo espontáneo y libre y ni la espontaneidad y la libertad se podían practicar en esos años de manera profesional. Si uno de nosotros hacía un chiste demasiado incómodo no nos podían amenazar con dejarnos sin trabajo porque, a diferencia de los guionistas y actores de televisión, no vivíamos de eso. Viví ese movimiento casi desde sus inicios (aunque la Seña existía desde antes de que hubiera un movimiento como tal) y lo recuerdo con muchísimo cariño. Gente muy talentosa, ambiciosa y competitiva pero con mucha generosidad para reconocer el talento ajeno. Creadores muy atentos a quien se apareciera con algo verdaderamente novedoso, a reconocerlo y a tratar de superarlo la próxima vez que se encontraran en el próximo festival. No había público más atento a lo que hacía un humorista que el resto de nosotros y eso nos hizo aprender mucho en muy poco tiempo.

Por otra parte, tú puedes formar un actor o un dibujante pero el humor es un impulso que nace con él. Por lo que he dicho anteriormente y por otras condiciones -en las que incluiría desde la perestroika, con el poquito de libertad que trajo, y la crisis siguiente que se conoce como Período Especial, con la desesperación y la rabia que trajo- favorecieron que este movimiento continuara creciendo a un nivel limitado pero consistente. Hasta encontrarte que, treinta años después, la mayoría de los humoristas cubanos más importantes de la actualidad comenzó como parte de ese movimiento.

PP: Estoy de acuerdo contigo. Sólo te señalo que cuando surgió nuestra Seña del Humor, no conocía a Les Luthiers, ni a casi nadie que vibrara en esa frecuencia que tanto nos interesaba en el humor. Quizás recuerdo “¿Dónde está el piloto” (bandera del humor ZAZ), que me sorprendió un sábado a las 12 a.m. por TV en una noche aburrida de provincia y cosas aisladas así. Y lo que realmente recuerdo me estimuló fueron las apariciones sobreactuadas por TV de Carlos Ruiz de la Tejera, con sus monólogos de la “vela”, del vals del minuto y los textos de Zumbado. Y reafirmo lo que dices de que una de las virtudes de los humoristas de esos años 80 fue su camaradería, su cero envidia, cero competencia, etc.. Algo nada despreciable si vemos lo que siempre ha demostrado el medio, sea en Cuba o donde sea. Y aprovecho para abordar otro tema que me vino a la mente.

En la actualidad está de moda el stand up comedy. Como vives en Estados Unidos, sé que conoces a los más importantes exponentes del género. ¿Pero conoces a los comediantes latinos? ¿Te has enterado de que esa modalidad está pasando por su mejor momento en Latinoamérica? Sin embargo, muchos de sus “militantes” se paran frente a un micrófono y dicen textos sin dramaturgia, sin usar elementos de actuación, y en una actitud de sabérselas todas, con soberbia, de estar por encima del Bien y el Mal, y hacen casi sólo burlas ácidas, donde agreden y hasta humillan a sus víctimas, incluso hasta se permiten espacios donde hablan en serio en sus presentaciones sobre política o de cualquier tema de la actualidad y siempre con muchas obscenidades y vulgaridades, claro. Y por si no lo sabes, también “teorizan” y aseguran públicamente que ese el verdadero humor, que es el único que hace reír en estos tiempos y que ya se terminó la época del humor blanco. Bueno, esta larga introducción es para preguntarte, ¿podrías reflexionar y teorizar sobre lo que acabo de contarte?

ENRISCO: No me considero especialista en humor latinoamericano pero si debo hablar de eso preferiría empezar por tener en cuenta todo el humor que se hace en español, no solo el de Latinoamérica. Porque en España se dio el fenómeno de pasar de unos pocos grupos humorísticos, algunos bastante anticuados, a ese fenómeno que es el Club de la Comedia que ha dado voz a un grupo importante de comediantes entre los que están Dani Rovira, Eva Hache, Leo Harlem o Goyo Jiménez que consiguen ser al mismo tiempo complejos y sutiles y tremendamente populares. Y es que es un formato muy rentable: un comediante y un micrófono que va probando sus chistes a distintos niveles hasta lograr una obra bien acabada, sólida.

Entre el humor latinoamericano no cubano lo mejor que he visto en los últimos años, con distancia, son los programas de Peter Capusotto y los cortos de los brasileños de Porta dos Fondos que consiguen combinar inteligencia y audacia humorística en las dosis que me recomienda el médico. Fuera de eso seguramente tú puedas recomendarme muchos nombres porque casi todo lo que he visto han sido especiales de Netflix y no todos me dejan un buen sabor. De lo que he visto además de unos brasileños muy buenos (Thiago Ventura, Mher Marrer, Afonso Padilha) están el mexicano Carlos Ballarta y los argentinos Marcelo Wainrach y Agustín Aristarán: todos son humoristas que dentro del estilo de cada cual empiezan por respetar la inteligencia del espectador. Sin embargo, se echa en falta lo que en la década de los setenta y ochenta consiguió el talento colectivo de Les Luthiers. Porque ese sistema de colaboración colectiva consigue una complejidad y una textura en el humor que es casi imposible conseguir de manera individual y lo que más se le acerca en calidad a Les Luthiers, aunque con un estilo muy distinto, es Porta dos Fundos.

Recuerdo que cuando empezaba el movimiento de humoristas cubanos de los ochenta anunciaban a muchos de sus grupos como que hacían “humor inteligente” y a mí esa fórmula siempre me pareció redundante. Para que el humor lo sea de verdad tiene que ser inteligente, entender la realidad, y luego moverla de lugar, sorprendernos con una nueva versión de ella. Y para eso tiene que valerse de todos los recursos que tiene a mano: el ingenio verbal, la actuación, la dramaturgia. Pienso que lo mejor que se puede hacer con el humor es no limitarlo y valerse incluso del grotesco y de la vulgaridad si hace falta, pero como un recurso más. Sucede que, con tantos tabúes con los que vivimos, somos como niños pequeños a los que les prohíben todo y, en cuanto pueden, se ponen a decir todas aquellas palabras prohibidas. Eso es fatal porque la vulgaridad y el grotesco pueden usarse en el humor pero son incapaces de sustituirlo, como tampoco pueden sustituir la inteligencia, el ingenio.

Tampoco la complicidad puede substituir al humor. Sucede que con un público cómplice cualquier cosa que digas sobre el tema apropiado va a ser saludada con carcajadas. El reto del humor es justo lo contrario, hacer reír incluso a aquellos que no sienten especial complicidad contigo. O un reto todavía mayor: hacerlos que se rían de aquello que se toman en serio. Dicho esto, debo confesar que no entiendo mucho que es eso de humor “blanco”: para mí el humor siempre se mete contra alguna preconcepción. Y una de las preconcepciones más sólidas que tenemos son nuestros presupuestos lógicos y gramaticales. Y eso que llaman “humor blanco” pone a prueba esa lógica y esa gramática. Por lo demás no me gusta el humor insulso. Con el humor me pasa como con el queso: soy de sabores fuertes.

PP: Sí, te puedo mencionar otros, sobre todo sudamericanos muy buenos (en Netflix veo más humoristas que no me gustan que los que sí), y te confieso que soy fanático a “Porta dos Fundos”. En cuanto a lo que señalas sobre el humor, te digo que son puras convenciones, amigo mío. Yo no pienso como tú. Mejor dicho, sé a lo que te refieres y coincido contigo, pero me gusta formularlo de otra manera. Para mí un payaso de circo es un humorista porque hace humor, un comediante cuyo personaje se esconde en el closet porque lo pilla el marido de su compañera de cama, hace humor, el que escribe, dibuja, escenifica, o cuenta un simple chiste es un humorista, etc..

ENRISCO: Yo respeto a los payasos pero para mí un tipo que se pone una peluca de mujer y piensa que por eso la gente debe reírse no es humor. O hay gente que le encanta reírse cuando abusan de alguien y eso tampoco es humor. Respeto a todos los humoristas pero no todo el que hace reír lo es. Piensa en lo mucho que la gente le ríe las pesadeces a los jefes.

PP: Es cierto, no todas las risas es producto de lo cómico. Pero yo me refería a los humoristas que son los que hacen humor, obvio. Los otros no me interesan. Los ejemplos que mencionas no los clasifico como humor, ni subirse a un escenario en Cuba y decir “¡Qué hambre hay!” o cosas así. O el que diga en público una mala palabra sin necesidad, o decirle sólo “gordo” o “gorda” a una persona y así mil ejemplos más. Lo que hacen o dicen eso no son humoristas, obviamente. Pero los artistas que crean humor –para mí, repito-, solamente los diferencia entre sí la calidad y el nivel de elaboración artística. Y la otra arista de este asunto: si califico algo de humorismo, lleva implícito que es cómico en alguna medida, o no fuera humor. Lo que los diferencia de la obra de Buster Keaton, Chaplin, Twain, Chesterton, Les Luthiers, Quino, Allen, Monty Python, etc., es la calidad del humor, repito. Por ese motivo me da sentido lo de “humor inteligente”, aunque no sé muy bien qué significa exactamente. Y por otra convención acepto lo de “humor blanco”, cuya definición para mí es: el que provoca risa o sonrisa sana e inocente, sin referencias a sexo, burlas, sátiras, etc.. Con decirte que me encanta reír por reír, como símil a “el arte por el arte”. Creo que incluso es más difícil ese humor “blanco” que digo, que el de muchos otros basado en la burla y la sátira.

ENRISCO: Yo no creo que haya risa inocente: incluso en los chistes más ingenuos, esos que les cuentan los padres a los niños pequeños hay una picardía, una pequeña subversión de lo aceptado como correcto. Los meros juegos de palabras son una subversión de las reglas gramaticales. Pero una subversión momentánea. Porque el humor no se propone cambiar la realidad. Apenas trata de jugar con ella y luego dejarla en su sitio. Aunque siempre termine haciéndole pequeñas hendiduras a los discursos serios, volviéndolos algo más porosos. Eso es lo que pasa en las situaciones más serias del mundo: en medio del velorio de alguien querido recordamos un viejo chiste y nos entran unos deseos inaguantables de reír y ya eso nos hace replantearnos la seriedad de la situación.

PP: Yo sí creo que hay risa inocente (recuerda que hay muchos tipos de risa además de la que produce el humor). Pero incluso en el humor, prefiero llamarle “inocente” a la que digo, como a la infantil, a la de reír por reír, a la que no es de burla, sexo, etc.. Me viene a la mente ahora Freud, el cual decidió un día clasificar los chistes de tendenciosos o no, sólo porque le venía bien a su teoría. Pues quisiera que me perdonaras y aceptaras esa convención mía. Pero insisto, en el fondo ambos tenemos razón y sé que decimos lo mismo. En fin, se puso algo denso el intercambio por mi culpa... Cambio entonces: ¿es verdad la acuñada frase: "Es más fácil hacer llorar que hacer reír?

ENRISCO: Depende. La lágrima difícil, la profunda, es tan difícil y rara como la risa inteligente. La sensiblería melodramática en cambio es bastante más fácil hasta que la risa boba.

PP: ¿Alguna anécdota relacionada con nuestra profesión?

ENRISCO: Acababa de llegar a España y había solicitado asilo político así que entre los lugares a los que tuve que acudir al CESID (algo así como la CIA española) a explicar "mi caso". Básicamente te citaban para analizar la credibilidad de tu historia. Me rodeaban tres o cuatro agentes, tipos que no contratan para parecer simpáticos y aquello más que una entrevista parecía un interrogatorio. Estaba contándole mi historia pero luego cambié de idea y comencé a leerles un cuento que había publicado en una revista. Podría parecer una locura ir al búnker de la policía secreta a leer un cuento pero ya al final del primer párrafo estallaron en carcajadas. Enseguida me dijeron que entendían y no me quedó claro si entendían que era humorista o que alguien que escribía cosas así merecía ser perseguido por un régimen con poco sentido del humor. Y lo curioso era que esos tipos eran muy parecidos a los tipos que vigilaban y amenazaban a uno en Cuba por leer en público esos mismos cuentos.

PP: Bueno, finalizo este interesantísimo diáloco con una pregunta que acostumbro a hacer siempre, desde que le agarré el gusto a dialocar con mis colegas favoritos: ¿se te ocurre una pregunta que deseaste te hubiera hecho? Y si es así, ¿puedes responderla?

ENRISCO: Echo en falta la vieja pregunta de los orígenes. ¿De dónde sale esa vocación por reír y hacer reír de todo? Eso siempre me da mucha curiosidad. Y en mi caso específico ¿de dónde sale ese estilo mío, tan asentado en la ironía y el sarcasmo? Y la mejor manera de responderla es -imitando a Freud- echándole la culpa a mi madre. Porque mi lengua materna no es el español. Mi lengua materna es la ironía, el sarcasmo. Mi madre, un ser muy inteligente que se pasó la vida enseñando literatura y cine, no te dice una frase sin darle tres o cuatro sentidos a la vez. Sus conversaciones tienen el filo de un sable de samurai cruzado con navaja suiza porque corta en todas direcciones, de muchas maneras distintas. El primer chiste que recuerdo me lo hizo ella: el del tipo que va a pedir la mano de Rosita al padre y el padre le pregunta por el salario gana y cuando el pretendiente le responde el padre exclama “Eso no le alcanza a Rosita ni para comprar papel sanitario”. Tiempo después el pretendiente consigue un aumento de salario y vuelve a pedir la mano pero el padre le responde lo mismo: “Eso no le alcanza a mi hija ni para comprar papel sanitario”. Y así hasta que el pretendiente se encuentra con la muchacha y le grita “Rosita: cagona”.

Oír a mi madre, una mujer de lo más educada y correcta, contarme aquel chiste cuando yo tenía cuatro años debió ser tremendo para mí. Por algo lo recuerdo todavía: a esa edad debió ser como una revelación. Existía un espacio donde lo que no te dejaban decir normalmente era aceptable y hasta divertido. Y luego en mi casa había una buena biblioteca y, entre las novelas de Julio Verne y Salgari, antes de los diez años ya me había leído el Decamerón que es toda una lección de lo bien que la gente se lo podía pasar en medio de la peste bubónica. Y Las mil y una noches, con toda su picaresca. Aunque en todo lo demás seguía siendo el niño más inocente del mundo pero ya había leído cuentos en que las monjas se volvían locas fornicando con el jardinero del convento. Después de eso ya nada vuelve a ser igual: todavía no tenía idea de qué era el sexo pero ya sabía que era divertidísimo.

Y muy poco después apareció Virulo con su Historia de Cuba cantada. Cuando la cantó por televisión -estaría en quinto o sexto grado- la grabé y me la aprendí de memoria. Y el libro Limonada del grandísimo Héctor Zumbado fue otra epifanía. Zumbado para describir lo malo que era el pan que vendían en Cuba te hablaba de Kant, con la mayor naturalidad del mundo. Y el libro Salaciones del Reader's Indigest de Marcos Behemaras y las Aventuras del soldado desconocido de Pablo de la Torriente Brau y todo lo que pude encontrar de Mark Twain, sobre todo esos cuentos en los que el humor está más concentrado: “El duelo francés” “El robo del elefante blanco”, cosas así. Ya a los 12 años me había empachado con todo eso. A partir de ahí que viniera lo que fuera. Y vino. Porque el humor, como cualquier droga, te obliga a consumir dosis cada vez más fuertes.

Pero si insisto en lo temprano que me atacó el bichito del humor no es para hacerme el precoz sino porque a pesar de eso me pasé media vida convenciéndome que mi vocación eran cosas serias como la historia. En el primer concurso literario “importante” que participé en 12no grado fue uno provincial al que iban los ganadores de sus respectivos municipios a leer sus escritos en persona: una buena oportunidad para estar fuera de mi internado por un día completo. Pues me pasé toda la competencia bromeando y burlándome de los concursantes pero cuando me llegó el momento de leer lo que traía solté unos poemas de lo más solemnes, horrorosos. Creo que alguien me dijo -seguramente fue una muchacha que son las que se dan cuenta enseguida de esas cosas y a las que hacemos caso a esa edad- que esperaba que leyera algo más acorde con mi personalidad. Y en eso estoy desde entonces: tratando de serme lo más fiel que pueda.

PP: Bueno, amigo mío, fue un gran placer este díaloco contigo. Queda pendiente un extenso intercambio teórico y te invito a que leas mi libro “Metahumorfosis. Vivencias y reflexiones de un humorista”, porque te asombrarás de lo parecido que fue la formación del sentido del humor de ambos. Espero que haya sido recíproco el placer al participar en este diáloco. Te agradezco de corazón que hayas aceptado perder tu valioso tiempo conmigo. Y deseo que tus éxitos se multipliquen y que nunca dejes de escribir. En mi mundo, ya te di hace rato el Premio Nacional de Humorismo.

Un abrazo.

Interview with Enrique del Risco "Enrisco"

By Pepe Pelayo

Humor as an elegant, sharp and penetrating weapon

I could introduce this colleague by copying the following from Wikipedia: “Enrique del Risco Arrocha, known as Enrisco (Havana, November 9, 1967), is a Cuban writer and humorist. Graduated in History of Cuba from the University of Havana, in 1990, and doctorate in Latin American Literature from New York University (NYU) in 2005. He resides in West New York, New Jersey, since 1997. He holds a lecturer position at New York University itself. He won the XX Fernando Quiñones Unicaja Novel Prize in 2018.”

But I can also present him as someone I admire for how he writes and for what he writes, whether for theater in the “belle époque” of humor in the 80s or for his published articles (I have not yet been able to read his award-winning novel). I follow him on his blog and I had the opportunity to spend time with him in New York after years without seeing him (since the end of the aforementioned decade), and I truly consider him a great Cuban humorist and a good person. So I regret not having developed a deeper friendship with him, although it was not the fault of either of us, just the paths of life.

As I expected, it was an honor and a pleasure to develop this dialogue with him.

PP: Are you aware that you are a reference in Cuban humor? That many people and especially the comedians of the boom of the 80s consider you great? That you are in the history of Cuban humor because of your books, because of “San Zumbado”, etc.? I imagine so, obviously. So the question is how do you feel about that? It's a responsibility, right? Have you tried to convince yourself that this is not the case? Anyway, how have you accepted that reality?

ENRISCO: A creator must take his work seriously but not himself. And if what you do is make humor, then with much more reason you should avoid those responsibilities such as being a reference for anyone. It is quite difficult not to disappoint the public, to live up to what they may expect from you. I think that if I have contributed anything, it is to help topics that were taken with overwhelming seriousness, such as Cuban history or politics, in a country with decades of dictatorship, be seen from a humorous perspective. While in Cuba politics was taboo and the allusions were very elliptical, in exile it was taken with a supremely serious tone. When I started doing humor - first in Cuba and then in exile with the column for the digital newspaper Cubaencuentro - what was done as political humor was mainly propaganda disguised as a joke. Many very good comedians shied away from politics not out of fear but because it seemed to them that it lowered the quality of what they did. If I had any merit it was to demonstrate once again - as other Cuban comedians had done in the past and I think first of all of the caricaturist Eduardo Abela - that politics was as good a subject to make humor with as any other. It is not exclusively my merit but I think I was one of those who did it with the greatest insistence.

After all, making humor is taking distance from things, a distance that allows you to see their ridiculous side, because there is nothing in this world that does not have a ridiculous side. Make fun of everything and not even take your own conclusions seriously but also laugh at them. The comedian - when he is consistent - is the most radical critic that exists because he laughs at everything, starting with himself. And humor is at the opposite extreme of the sacred. We need sacredness to give consistency to our lives. Normally people look for the sacred in religion, politics, ideologies but also in other things such as arts, beauty, sex or sports, something that pushes them to a variant of the sublime, because the sublime is something that we need one way or another. Humor, for its part, is one of the best instruments that have been invented to test the sacred, to correct its excesses. That is why absolutist and totalitarian systems, which want to invest themselves with a sacred mantle, find humor so uncomfortable.

PP: You're right, a creator should not take himself seriously. But whether you want it or not, you are a reference for many. It is also true that humor desacralizes and I would add that it desacralizes, as a nuance of desacralizing.

And now I quickly move on to another question. Without a doubt, political humor, or at least that related to Cuba, gives the impression that you are very interested, right? And what you have created in those fields you know has transcended. Would you like to venture into other types of humor apart from what you have already done? Is there something deep down in humor that you have never experienced and that you would like to do or achieve? Would you like to innovate, challenge yourself in a new style, a new modality, or other content? There are several questions, but answer them in a single answer.

ENRISCO: I have never been a humor professional. I have almost always written what I wanted when I wanted. When I grew up - in the seventies - we breathed, ate and shit politics. And by politics I mean that kind of religion that Castroism was in its first decades. On the street, at home, on television, at the movies, at school. Time was measured in years of Revolution, everything seemed to make sense only thanks to politics. That's why I have used humor as a detoxification mechanism after spending my entire childhood and adolescence exposed to those dogmas. Well used, humor is one of the best antidotes that have been invented against dogma poisoning. This may seem like a joke to you, but I have ended up discovering that I don't like politics. Real politics, the one practiced in democratic countries with parties with different programs, etc., leaves me quite indifferent. I have discovered that what I cannot stand is having my freedom restricted or my intelligence not being respected. That's why I practice humor as a way to confront the daily shame that your country has been under tyranny for sixty years, an amount of time that seems geological rather than political. But precisely because this situation has essentially not changed for so long, it is becoming increasingly difficult for me not to repeat myself when writing about Cuba.

I have asked myself if I can do something other than political humor and perhaps that is why I have been doing three consecutive soccer World Cups making humorous reviews of each match I watch, which is almost all of the 64 matches played in each World Cup, and publishing them. on my blog as I write them. In this way, I allow myself to play with a broader frame of reference than the one I use to make jokes about Cuban politics and give some meaning to the fact that every four years I spend a month in front of the television to watch three or even four games a day, as if it were a job. I have also been writing a humorous column for a New York newspaper for years about the history of the Latino presence in the city from its founding to date. It is a very pleasant job because history and New York are two topics that interest me very much.

I think that, more than politics itself, what interests me are social taboos, whatever they may be. That if I had grown up in Saudi Arabia I would mock the religious restrictions and machismo. I am not interested in working with topics that are usually considered comical, such as mothers-in-law or criticism of more or less harmless customs. Each society, no matter how liberal it believes itself, engenders its own taboos and it is against those taboos that I find, personally, meaning and emotion to write. For example, for a long time I have been planning to write a book of fables about political correctness, the new great taboo generated by North American society, in which I have lived for more than two decades, and which every day threatens to cut more spaces of freedom that is the air in which any comedian breathes. Because if I see any special commitment to humor, it is to fight to protect and expand freedom of expression and against restrictions of all kinds: religious, moral, logical and even linguistic. But not to destroy them - because humor alone is incapable of destroying anything - but to make them less suffocating than they are. It is not by chance that one of the greatest comedians in this country, Dave Chapelle, has recently dedicated all of his monologues more than to racism, as he did at the beginning of his career, to criticizing political correctness because, evidently, he sees it as more dangerous until the own racism.

PP: My question was more directed to whether you would like to write for radio, for TV, for cinema, or write to an actor, or do children's humor, or humor in commercials, or create jokes, or address new topics for you, etc. .. Anyway, would you do something you've never done before?

ENRISCO: In reality, I have done less commercials than everything: radio (with Ramón's program); cinema with Daniel Díaz Torres and also scripts for short films that were never filmed. On the other hand, I wrote a zarzuela (although I see more possibilities for it as a musical than as a zarzuela) with Paquito D'Rivera and Alexis Romay: “Cecilio Valdés, el Rey de La Habana” which has a lot of humor. I once did humor for television with Americatevé in Miami and I even wrote a children's play, “The Cook King,” which was premiered by a theater group in Havana in the 90s. I have also written texts to actors and theater groups who still replenish them from time to time. Or I wrote a four-handed fiction history of Cuba with Francisco García González: It's called Leve Historia de Cuba. And I wrote, on request, a series of biographies of Latin American heroes aimed at children. But serious. I am quite curious about everything that is proposed to me but in the end I feel more comfortable writing books, alone and about whatever I want.

PP: Well, I asked you the question for fun! Sorry, I just didn't know what you're telling me. Congratulations. All the more reason I feel proud to talk with you and to have not made a mistake in placing you in the “Olympus of Cuban Humor.” Of course, I had told you “something you have never done.”

Well, I move on to another related question: would you accept the National Humor Award in Cuba if it were awarded to you this year?

ENRISCO: No. And even less in a year in which the hunting season has opened against backyard comedians. It would be seen, and rightly so, as a lack of solidarity with my colleagues who are now being persecuted by state institutions and in Cuba all national awards are either granted by the State or at least it gives its approval. Furthermore, if officially in Cuba I do not exist, why would they give me an award? As a sign of tolerance? I have been outside my country for almost 25 years denouncing that dictatorship. Why would they give me an award? To demonstrate that the Cuban State not only tolerates but rewards its critics? What would be the point of accepting it? What I do comes with the price of not aspiring to any Cuban award because otherwise what are we talking about? Reward me for the same thing they punish the Cubans on the island? Accept an award in a country where people do not have access to the internet and cannot see, among so many much better things, what I do? This is serious? Is there a hidden camera?

And if they are going to award the National Prize for Humor in Cuba, let them start with Pible, with Ramón Fernández Larrea or with you, who started before me and have a quite notable career within Cuba. You answer the question and then tell me.

PP: First of all, thank you for mentioning my name in those supposed award candidates. But I asked you the question almost knowing your answer in advance, a bit to put my finger on it, because I have heard several colleagues talking about the matter and some think the same as you, but others claim that they are still Cubans and Cuban is humor. what they do, even though they live in another country and that is why they must be taken into account for these awards. It is like the famous and recurring controversy of whether or not artists should go to Cuba to offer their art.

Now I'll change the subject for you. Look, Cubans have always had a tradition in humorous music, because good composers and isolated performers have never stopped appearing. Graphic humor had its boom with the Dedeté, its prestige and its countless international awards, plus the support of the Museum of Humor and the San Antonio Biennials and later the Melaíto; However, no one can affirm that there was a massive phenomenon within graphic humor. But in the 80s something strange happened in stage humor: suddenly many comedians, screenwriters, etc. appeared, and all over the country. In Cuba there have always been great stage comedians, both in theater, on TV, radio and even in cinema, but they were figures. However, in the 80s the range opened up and many colleagues emerged. Was that a “Movement” for you? Why do you think that happened, especially since we are all amateur artists?

ENRISCO: Without a doubt it was a movement, one of the most important and one of the most undervalued in the cultural history of Cuba in recent decades, as is almost always the case with humor. Humor is like the town whore: everyone looks for it but no one gives it value. Or if you prefer a more elegant comparison, humor is like air or water that people don't value much but they also can't live without them. Nobody talks about it but in what they insist on calling the Gray Five Years - which actually covered the entire decade of the seventies, which was the most closed and repressive in Cuban history - humor was one of the most affected manifestations. In the seventies, everything from rock to most balladeers in Spanish was prohibited, but comedians were prohibited from laughing at the reality that surrounded them. Since everything was in the hands of the State, from transportation to cafeterias, mocking the taste of croquettes was questioning the State's ability to make them. It was the time when the main comedy program was one that made fun of the old republic. Comedians like Zumbado or Virulo became famous at the end of that decade for having the great audacity to make fun of croquettes and taxis. (Zumbado's case is complicated because his best-known texts are press articles that he wrote at the end of the sixties but would have been forgotten without the montages that Carlos Ruiz de la Tejera made later or the anthology that was published for Zumbado in 1978). In the eighties, a generation appeared for whom those limits were very narrow. And he realized that the humor that attracted us came from somewhere else: from Argentina like Les Luthiers, from England like Monty Python or from the United States like Woody Allen, the Zucker brothers or Mel Brooks. People - like the Seña del Humor de Matanzas that you founded yourself - who realized the void that existed and began to fill it in alternative spaces such as university festivals or clubs. It is not by chance that several of those first groups were named after games with the word “peña”: the Seña, the Leña, the Piña and even the Pena del humor. That is, this movement flourished in the spaces least controlled by a (political) system that despised humor and at the same time suspected its subversive capacity. Because humor, and I never tire of insisting on this, is subversive by nature. Of course, a playful subversion that does not aim to change the world but simply makes people laugh.

At that time we were all amateurs, that is, we were less contaminated by the inertia of the system but at the same time almost all of us had university preparation, we had studied different disciplines and in many cases we brought the richness of those disciplines to the field of humor: engineers, philologists, architects, art historians, psychologists. I was a historian myself. And we began to attract an increasingly broader audience, a generally educated audience that was fed up with the bland diet of humor we were being fed on television. It is no coincidence how long it took this movement to assault the mass media, to establish itself in them. First with a provincial radio station with Ramón's program and then, much later, on television, with the program “Sabadazo”. But this movement is already reaching television in a very controlled, over-water manner. Nothing to do with what was happening in the theater. Because that highly sophisticated and critical humor that was made in the theater in the eighties, when it finally reaches television, does so in the traditional molds of manners humor, slapstick theater, etc.

The humor movement of the eighties was amateur in part because humor is something spontaneous and free and not even spontaneity and freedom could be practiced professionally in those years. If one of us made a joke that was too uncomfortable, they couldn't threaten to put us out of work because, unlike television screenwriters and actors, we didn't make a living from it. I lived through that movement almost from its beginnings (although the Seña existed before there was a movement as such) and I remember it with great affection. Very talented, ambitious and competitive people but with a lot of generosity to recognize the talent of others. Creators very attentive to whoever came up with something truly new, to recognize it and try to surpass it the next time they meet at the next festival. There was no audience more attentive to what a comedian did than the rest of us and that made us learn a lot in a very short time.

On the other hand, you can train an actor or a cartoonist but humor is an impulse that is born with him. Because of what I have said before and because of other conditions - which I would include from perestroika, with the little bit of freedom that it brought, and the following crisis known as the Special Period, with the desperation and rage that it brought - favored this movement will continue to grow at a limited but consistent level. Until you find that, thirty years later, most of today's most important Cuban comedians began as part of that movement.

PP: I agree with you. I'm just pointing out that when our Sign of Humor emerged, I didn't know Les Luthiers, or almost anyone who vibrated at that frequency that interested us so much in humor. Maybe I remember “Where is the pilot” (ZAZ humor banner), which surprised me on a Saturday at 12 a.m. on TV on a boring night in the province and isolated things like that. And what I really remember stimulated me were the overacted appearances on TV of Carlos Ruiz de la Tejera, with his monologues of the “vela”, the waltz of the minute and the texts of Zumbado. And I reaffirm what you say that one of the virtues of the comedians of those 80s was their camaraderie, their zero envy, zero competition, etc. Something not insignificant if we see what the medium has always demonstrated, be it in Cuba or wherever. be. And I take this opportunity to address another topic that came to mind.

Stand up comedy is currently fashionable. Since you live in the United States, I know that you know the most important exponents of the genre. But do you know Latin comedians? Have you heard that this modality is going through its best moment in Latin America? However, many of its “militants” stand in front of a microphone and say texts without dramaturgy, without using acting elements, and in an attitude of knowing it all, with pride, of being above Good and Evil, and they do almost only acidic mockery, where they attack and even humiliate their victims, they even allow spaces where they speak seriously in their presentations about politics or any current topic and always with many obscenities and vulgarities, of course. And in case you don't know, they also "theorize" and publicly assure that this is true humor, that it is the only one that makes people laugh these days and that the era of white humor is over. Well, this long introduction is to ask you, could you reflect and theorize about what I just told you?

ENRISCO: I don't consider myself a specialist in Latin American humor, but if I have to talk about it I would prefer to start by taking into account all the humor that is done in Spanish, not just that of Latin America. Because in Spain there was the phenomenon of going from a few comedy groups, some quite old-fashioned, to that phenomenon that is the Comedy Club that has given voice to an important group of comedians among which are Dani Rovira, Eva Hache, Leo Harlem or Goyo Jiménez that manage to be at the same time complex and subtle and tremendously popular. And it is a very profitable format: a comedian and a microphone who tests his jokes at different levels until achieving a well-finished, solid work.

Among non-Cuban Latin American humor, the best I have seen in recent years, by far, are the programs by Peter Capusotto and the short films by the Brazilian Porta dos Fondos that manage to combine intelligence and humorous audacity in the doses that the doctor recommends. . Outside of that, surely you can recommend many names to me because almost everything I have seen has been Netflix specials and not all of them leave me with a good taste. From what I have seen, in addition to some very good Brazilians (Thiago Ventura, Mher Marrer, Afonso Padilha), there are the Mexican Carlos Ballarta and the Argentines Marcelo Wainrach and Agustín Aristarán: they are all comedians who, within each one's style, begin by respecting intelligence of the viewer. However, what the collective talent of Les Luthiers achieved in the 1970s and 1980s is missing. Because this system of collective collaboration achieves a complexity and texture in humor that is almost impossible to achieve individually and what is closest in quality to Les Luthiers, although with a very different style, is Porta dos Fundos.

I remember that when the movement of Cuban comedians began in the eighties, they announced many of their groups as doing “intelligent humor” and that formula always seemed redundant to me. For humor to be truly humorous, it has to be intelligent, understand reality, and then move it around, surprising us with a new version of it. And to do that he has to use all the resources he has at hand: verbal ingenuity, acting, dramaturgy. I think that the best thing to do with humor is not to limit it and even use the grotesque and vulgarity if necessary, but as another resource. It happens that, with so many taboos we live with, we are like little children who are prohibited from doing everything and, as soon as they can, they start saying all those forbidden words. This is fatal because vulgarity and grotesque can be used in humor but they are incapable of replacing it, nor can they replace intelligence and wit.

Nor can complicity replace humor. It happens that with a complicit audience, anything you say on the appropriate topic is going to be greeted with laughter. The challenge of humor is just the opposite, making even those who do not feel special complicity with you laugh. Or an even bigger challenge: making them laugh at what they take seriously. That said, I must confess that I don't really understand what “white” humor is: for me, humor always goes against some preconception. And one of the strongest preconceptions we have are our logical and grammatical assumptions. And what they call “white humor” puts that logic and grammar to the test. Otherwise I don't like dull humor. With humor it happens to me like with cheese: I have strong flavors.

PP: Yes, I can mention others, especially very good South Americans (on Netflix I see more comedians that I don't like than those that I do), and I confess that I am a fan of “Porta dos Fundos”. As for what you point out about humor, I tell you that they are pure conventions, my friend. I don't think like you. Or rather, I know what you mean and I agree with you, but I like to phrase it another way. For me, a circus clown is a comedian because he makes humor, a comedian whose character hides in the closet because his bedmate's husband catches him, makes humor, the one who writes, draws, performs, or tells a simple joke is a comedian, etc.

ENRISCO: I respect clowns but for me a guy who puts on a woman's wig and thinks that's why people should laugh is not humor. Or there are people who love to laugh when someone is abused and that is not humor either. I respect all comedians but not everyone who makes people laugh is one. Think about how much people laugh at bosses' annoyances.

PP: It's true, not all laughter is a product of comedy. But I was referring to comedians who are the ones who make humor, obviously. The others don't interest me. I don't classify the examples you mention as humor, nor do I classify getting on stage in Cuba and saying “I'm so hungry!” or things like this. Or someone who says a bad word in public without need, or only says “fat” or “fat” to a person and so on, a thousand more examples. What they do or say is not comedians, obviously. But the artists who create humor – for me, I repeat – are only differentiated by their quality and level of artistic elaboration. And the other side of this matter: if I describe something as humorous, it implies that it is comical to some extent, or it is not humor. What differentiates them from the work of Buster Keaton, Chaplin, Twain, Chesterton, Les Luthiers, Quino, Allen, Monty Python, etc., is the quality of humor, I repeat. For that reason, “intelligent humor” makes sense to me, although I don't know exactly what it means. And by another convention I accept "white humor", whose definition for me is: that which provokes a healthy and innocent laugh or smile, without references to sex, mockery, satire, etc. By telling you that I love to laugh for the sake of laughing, as simile to “art for art’s sake.” I think that the “white” humor that I say is even more difficult than that of many others based on mockery and satire.

ENRISCO: I don't believe there is innocent laughter: even in the most naive jokes, those that parents tell young children, there is mischief, a small subversion of what is accepted as correct. Mere puns are a subversion of grammatical rules. But a momentary subversion. Because humor does not set out to change reality. He just tries to play with it and then leave it in its place. Although it always ends up making small indentations in the serious speeches, making them somewhat more porous. That's what happens in the most serious situations in the world: in the middle of a loved one's wake we remember an old joke and we get an unbearable desire to laugh and that makes us rethink the seriousness of the situation.

PP: I do believe that there is innocent laughter (remember that there are many types of laughter besides that produced by humor). But even in humor, I prefer to call "innocent" what I say, like childish, laughing for the sake of laughing, what is not mocking, sex, etc. Freud comes to mind now, the who one day decided to classify jokes as biased or not, just because it suited his theory. Well, I would like you to forgive me and accept that convention of mine. But I insist, deep down we are both right and I know we say the same thing. Anyway, the exchange got a little dense because of me.

So, I end this very interesting dialogue with a question that I always ask, ever since I got the pleasure of talking with my favorite colleagues: can you think of a question that you wish I had asked you? And if so, can you answer it?

ENRISCO: I miss the old question of origins. Where does this vocation to laugh and make people laugh at everything come from? That always makes me very curious. And in my specific case, where does that style of mine come from, so based on irony and sarcasm? And the best way to answer it is - imitating Freud - by blaming my mother. Because my native language is not Spanish. My native language is irony, sarcasm. My mother, a very intelligent being who spent her life teaching literature and cinema, does not tell you a sentence without giving it three or four meanings at the same time. His conversations have the edge of a samurai sword crossed with a Swiss army knife because it cuts in all directions, in many different ways. The first joke I remember was made by her: the one about the guy who goes to ask Rosita's hand for Rosita's father and the father asks him about the salary he earns and when the suitor answers him the father exclaims "That's not even enough for Rosita to pay." buy toilet paper.” Some time later the suitor gets a salary increase and asks for her hand again, but the father responds the same: “That's not enough for my daughter to even buy toilet paper.” And so on until the suitor meets the girl and yells at her, “Rosita: cagona.”

Hearing my mother, a most educated and correct woman, tell me that joke when I was four years old must have been tremendous for me. There's a reason I still remember it: at that age it must have been like a revelation. There was a space where what they didn't let you say was normally acceptable and even funny. And then in my house there was a good library and, among the novels of Jules Verne and Salgari, before I was ten years old I had already read the Decameron, which is a lesson in how much fun people could have in the middle of the world. bubonic plague. And The Thousand and One Nights, with all its picaresque. Although in everything else he was still the most innocent child in the world, he had already read stories in which the nuns went crazy by fornicating with the convent's gardener. After that nothing will be the same again: I still had no idea what sex was but I already knew it was fun.

And very shortly after, Virulo appeared with his sung History of Cuba. When he sang it on television - I was in fifth or sixth grade - I recorded it and learned it by heart. And the book Lemonade by the great Héctor Zumbado was another epiphany. Buzzed to describe how bad the bread they sold in Cuba was, he spoke to you about Kant, with the greatest naturalness in the world. And the book Salaciones del Reader's Indigest by Marcos Behemaras and the Adventures of the Unknown Soldier by Pablo de la Torriente Brau and everything I could find by Mark Twain, especially those stories in which the humor is more concentrated: “The French Duel” “The theft of the white elephant”, things like that. By the time I was 12, I had become overwhelmed with all of that. From there whatever came. And wine. Because humor, like any drug, forces you to consume increasingly stronger doses.

But if I insist on how early the humor bug attacked me, it is not to act precocious but because despite that I spent half my life convincing myself that my vocation was serious things like history. The first “important” literary contest I participated in in 12th grade was a provincial one where the winners from their respective municipalities went to read their writings in person: a good opportunity to be away from my boarding school for a full day. Well, I spent the entire competition joking and making fun of the contestants, but when the time came to read what I had brought, I released some of the most solemn, horrifying poems. I think someone told me - it was probably a girl who is the one who quickly realizes these things and who we pay attention to at that age - that they hoped I would read something more in line with my personality. And that's what I've been doing since then: trying to be as faithful as I can.

PP: Well, my friend, it was a great pleasure to have this crazy conversation with you. An extensive theoretical exchange remains pending and I invite you to read my book “Metahumorfosis. Experiences and reflections of a comedian”, because you will be amazed at how similar the formation of both of their senses of humor was. I hope that the pleasure in participating in this dialogue has been reciprocal. I sincerely thank you for agreeing to waste your valuable time with me. And I wish that your successes multiply and that you never stop writing. In my world, I already gave you the National Humor Award a while ago.

A hug.

(This text has been translated into English by Google Translate)